Commentary from Our CIO—Year-End 2020

Back in April’s commentary, which feels like years ago when only nine months have passed, we recognized that we were living through an incredible period of history. The pandemic weighed heavily on us then and still does. But this quarter, we look back at what we’ve come through and lay out our investment outlook for 2021 and beyond. While many risks remain, the effective vaccines that are starting to be distributed provide a real light at the end of the tunnel.

We said in the first quarter that we would get through this crisis and that things would improve and recover. Financial markets recovered first, quicker than they ever have from such a deep economic hole and quicker than anyone could have hoped. Economies have made great progress too but are not back to their pre-COVID-19 levels yet and may not be for another year or two. On the health side, the authorities warn us we may be in for dark days this winter before the vaccines can be widely available to the general populace. This may set back economies and markets in the near term and keep us isolated and sheltering in place in some cases. But we expect that 2021 will see the end of the pandemic, and our society can then follow markets and the economy in bouncing back as well.

In the meantime, our wish remains the same as it was in April, that you and your loved ones stay safe and healthy.

Fourth Quarter & 2020 Market Recap

As we close out a tragic and turbulent year here’s where the financial markets stand.

Global stocks ended the year at all-time highs with a 16.3% gain. It hardly needs saying, but during the dark days of March, with pandemic fears rampant and the global economy falling off a cliff, very few if any market observers would have predicted this outcome. We wouldn’t have either, but then, we avoid short-term market predictions about any event. What we did write in concluding our first quarter investment commentary was: “Stay the course.” This is generally wise (albeit clichéd) advice for long-term investors following a disciplined investment strategy. And it proved prescient once again.

In 2020, U.S. stocks led the major equity markets. Larger-cap U.S. stocks gained 18.2% and smaller-cap U.S. stocks shot up 20.0% for the year. Developed international stocks gained 9.7%. Emerging-market (EM) stocks rose 15.2%.

In the fourth quarter, foreign stock markets were particularly strong, with gains in the mid-teens, outperforming the S&P 500 by several percentage points. Value stocks also beat growth stocks and small caps crushed large caps. Riskier assets in general got a boost from the resolution of presidential election uncertainty (at least for the most part, if not yet fully) and surprisingly positive Phase 3 COVID-19 vaccine results announced in early November.

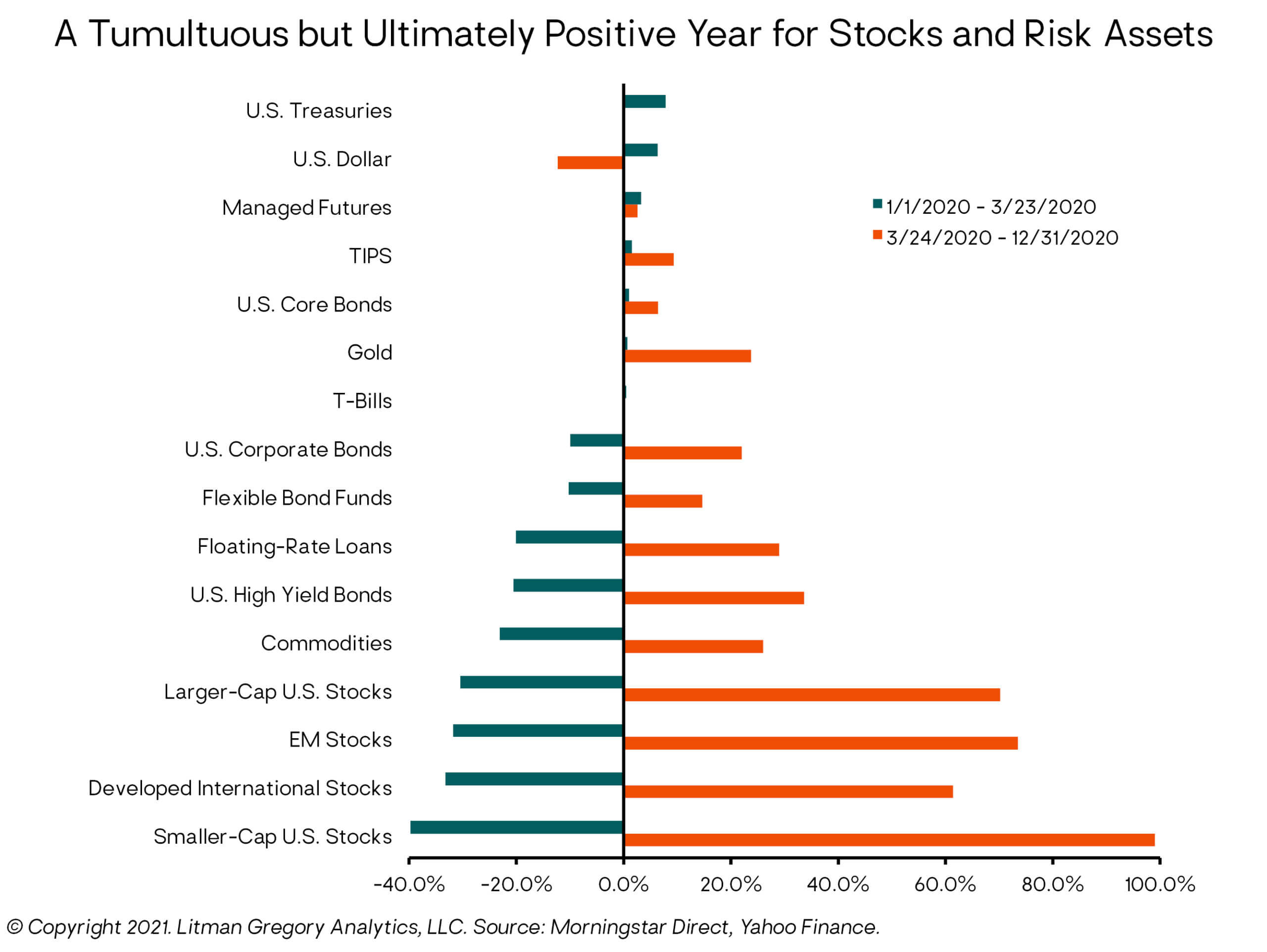

The comforting full-year returns masked the incredible volatility and stress investors faced earlier in the year. As the chart below shows, stock markets around the world were down between 30% and 40% from January 1 to the market bottom on March 23, in what was the quickest/sharpest bear market in history.  From the low point, stocks skyrocketed into year-end. The S&P 500, developed international, and EM stock indexes all roared back more than 65%. Small-cap U.S. stocks soared nearly 100%.

From the low point, stocks skyrocketed into year-end. The S&P 500, developed international, and EM stock indexes all roared back more than 65%. Small-cap U.S. stocks soared nearly 100%.

Moving on to fixed-income, core investment-grade bonds gained a strong 7.6% for the year, providing positive returns both during and after the market crisis period. The 10-year Treasury yield touched an all-time low of 0.5% in August and ended the year at 0.93%, roughly a full percentage point below where it started 2020.

In the credit markets, high-yield bonds and floating-rate loans posted 6.2% and 3.1% gains, respectively, for the year. Both asset classes materially outperformed core bonds during the last three quarters of the year, but still have some ground to make up from the tremendous credit market dislocations in March before the Federal Reserve rode to the rescue.

Key Drivers of Our 2020 Portfolio Performance

In a challenging and chaotic year, we are pleased to report our portfolios performed well.

We made two tactical changes to our portfolio allocations during the year, both of which added value. In mid-March, as stocks were plunging and investor fear was rampant, we added an increment (3%–4%) back to our U.S. equity exposure, funded from selling lower-risk assets in the portfolio that had held up much better on the downside. The S&P 500 is up over 50% from that trade date.

In early May, we swapped our small tactical European stock position into EM stocks, creating a “full” fat pitch overweight to EM stocks, funded from an underweight to U.S. stocks. Since then, EM stocks have outperformed both European and U.S. stocks (by roughly eight and 11 percentage points, respectively), boosting portfolio returns.

More broadly, our portfolios produced strong performance in the second half of the year as financial markets recovered from the sharp, pandemic-induced selloff and started looking ahead to a global economic recovery. In addition to our EM equity overweight, we benefited from the aggregate outperformance of our active equity and fixed-income/bond fund managers relative to passive index benchmarks. Our alternative strategies allocations generated absolute returns meaningfully higher than core bonds while trailing the strong equity market rebound, as we’d expect.

We are optimistic that this recent portfolio performance is the beginning of a more sustained trend: that prior years’ macro and market headwinds may be turning into tailwinds for our portfolio positioning. As discussed in our outlook below, we see good reason for optimism in this regard and for our patience and discipline to be rewarded. Of course, there are always uncertainties and risks, and we discuss those as well.

Macro & Market Outlook: 2021 & Beyond—Reasons for Optimism

Macroeconomic Backdrop & Outlook

The Pandemic

Unfortunately, any discussion of the big-picture outlook must still begin with the COVID-19 health crisis and its recent “third wave” resurgence in the United States and second wave surge in many other countries, particularly across Europe. The public health impact in the United States is increasingly severe, reaching all-time highs in daily deaths (3,800-plus) and current hospitalizations (130,000-plus). ![]()

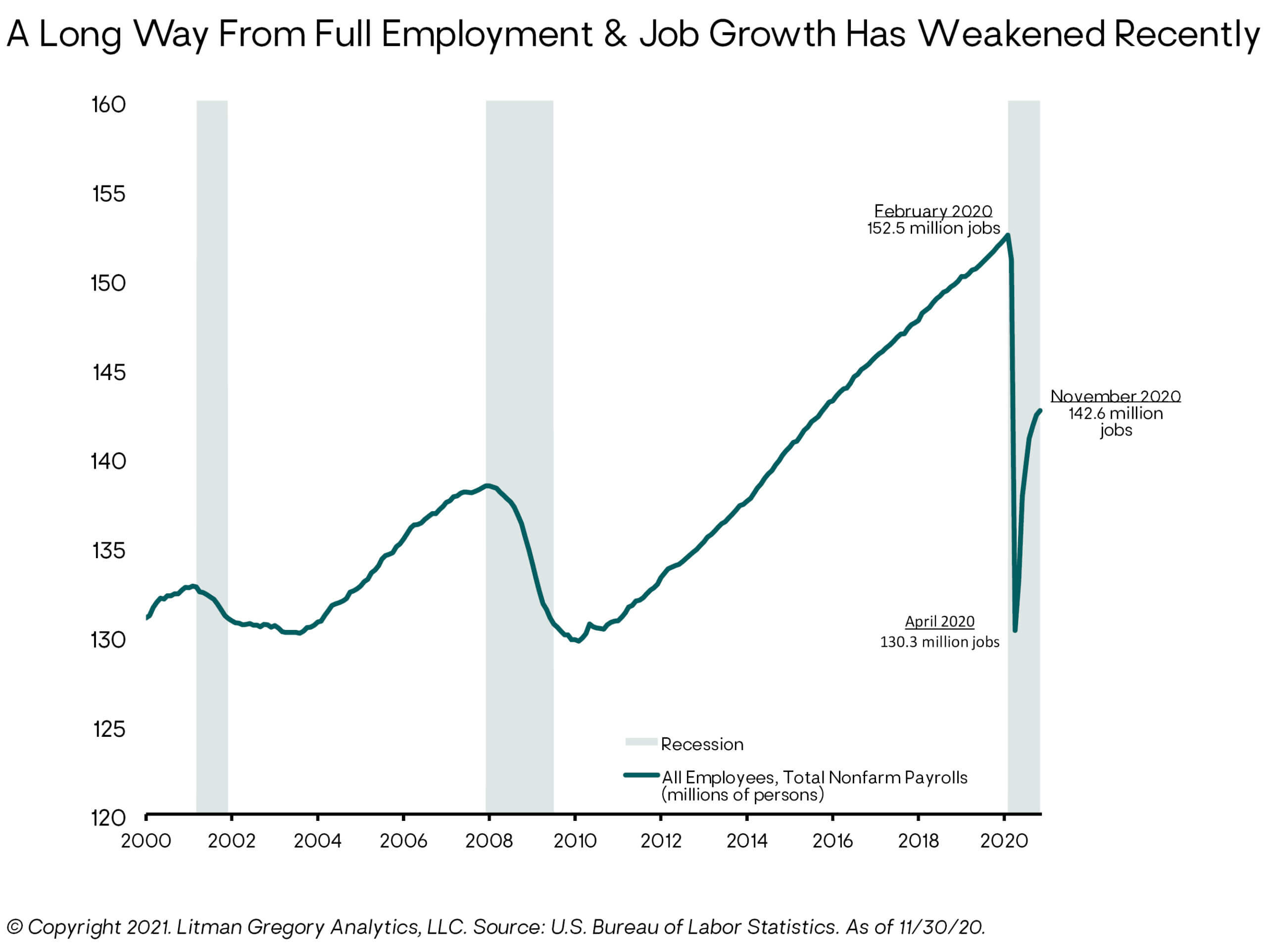

This is leading to increasingly aggressive—albeit still localized—economic lockdowns across the country. And that raises the risk of a sharp slowdown in the economy, if not an outright contraction, heading into 2021. Recent weak labor market data (weekly initial claims for unemployment insurance have been rising again), falling household income (down 1.1% in November), and slumping retail sales (down 1.1% in November, the largest decline since April and the biggest November monthly drop since 2008) indicate this is already happening. At their mid-December meeting, the Fed reiterated yet again that “the path of the economy will depend significantly on the course of the virus.”

Along with the pandemic surge, the expiration of emergency federal aid programs for individuals and small businesses is contributing to the economic slowdown. For this discussion we are putting aside the undeniable human suffering. For example, the poverty rate in the United States has increased from 9.3% in June to 11.7% in November—an increase of 7.8 million Americans falling into poverty as benefits from the previous COVID-19 relief package lapsed—even while the unemployment rate improved from 11.1% to 6.7%. Another sobering statistic: The number of American adults saying they live in a household that either “sometimes” or “often” doesn’t have enough to eat has risen sharply, by roughly six million (to 27 million total), compared to before the pandemic.

A lack of further government support would present a major near-term risk to the economy. Commenting on this situation in mid-December, Fed chair Jerome Powell said, “It looks like a time when what is really needed is fiscal policy.”

Thankfully, after months of political bickering and delay, congressional Republicans and Democrats reached agreement in the eleventh hour on a compromise $900 billion pandemic relief bill. Among its key provisions, it will make direct payments of $600 to qualifying individuals, extend $300 per week in extra unemployment benefits through mid-March, and authorize nearly $300 million in forgivable loans to small businesses. More fiscal aid may be requested in the early months of President-elect Joe Biden’s administration, including money for strapped state and local government budgets.

While the economy faces these very-near-term dangers, the likelihood of widespread distribution of effective vaccines in the first half of 2021 supports the case for a relatively strong economic rebound beginning in the second or third quarter—barring a derailment of the vaccine rollout or some other shock—as lockdowns are lifted and pent-up consumer and business spending is released.

This is a consensus view. For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) currently forecasts 5.2% global real GDP growth in 2021; this compares to a -4.4% global economic contraction in 2020 and 2.8% growth in 2019. For the U.S. and emerging economies, the IMF forecasts 3.1% and 6.0% real GDP growth, respectively, in 2021. Among some of the independent research services we subscribe to, Capital Economics forecasts 6.8% global GDP growth and 5% GDP growth for the United States; and Ned Davis Research forecasts 5.8% and 4.6%, respectively. These are all well above long-term historical average growth rates. The Fed is more conservative with a 4.2% U.S. GDP growth forecast for next year.

Monetary Policy

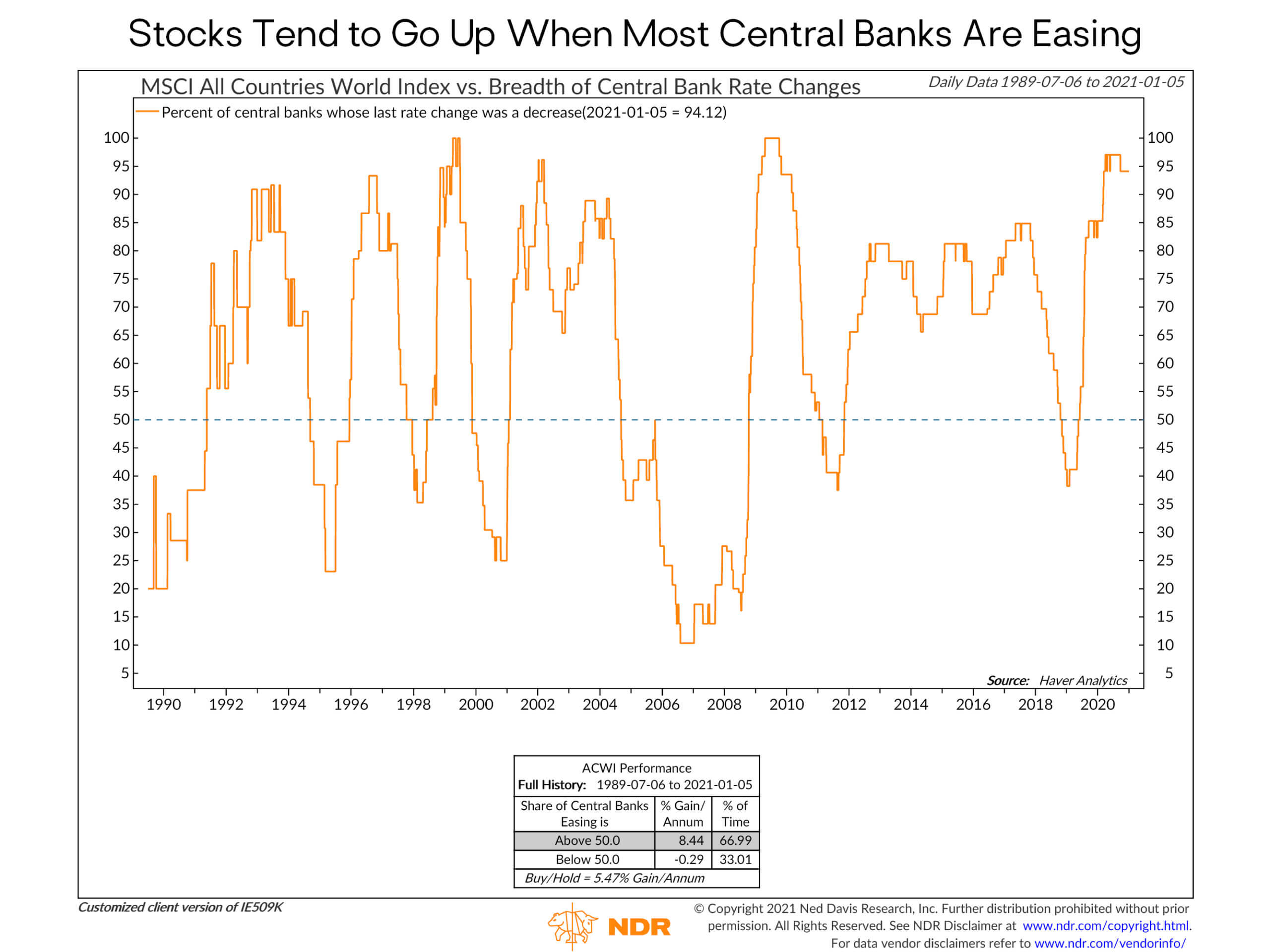

Critically, even if these forecasts are in the ballpark and we do get a decent economic recovery next year, monetary policy is almost certain to remain very accommodative/loose/stimulative. The Fed continues to communicate it is far (several years) from seeing a need to start tightening policy, either in terms of raising the federal funds rate (currently near zero) or reducing its quantitative easing (QE) asset purchases (currently at a rate of $120 billion per month).

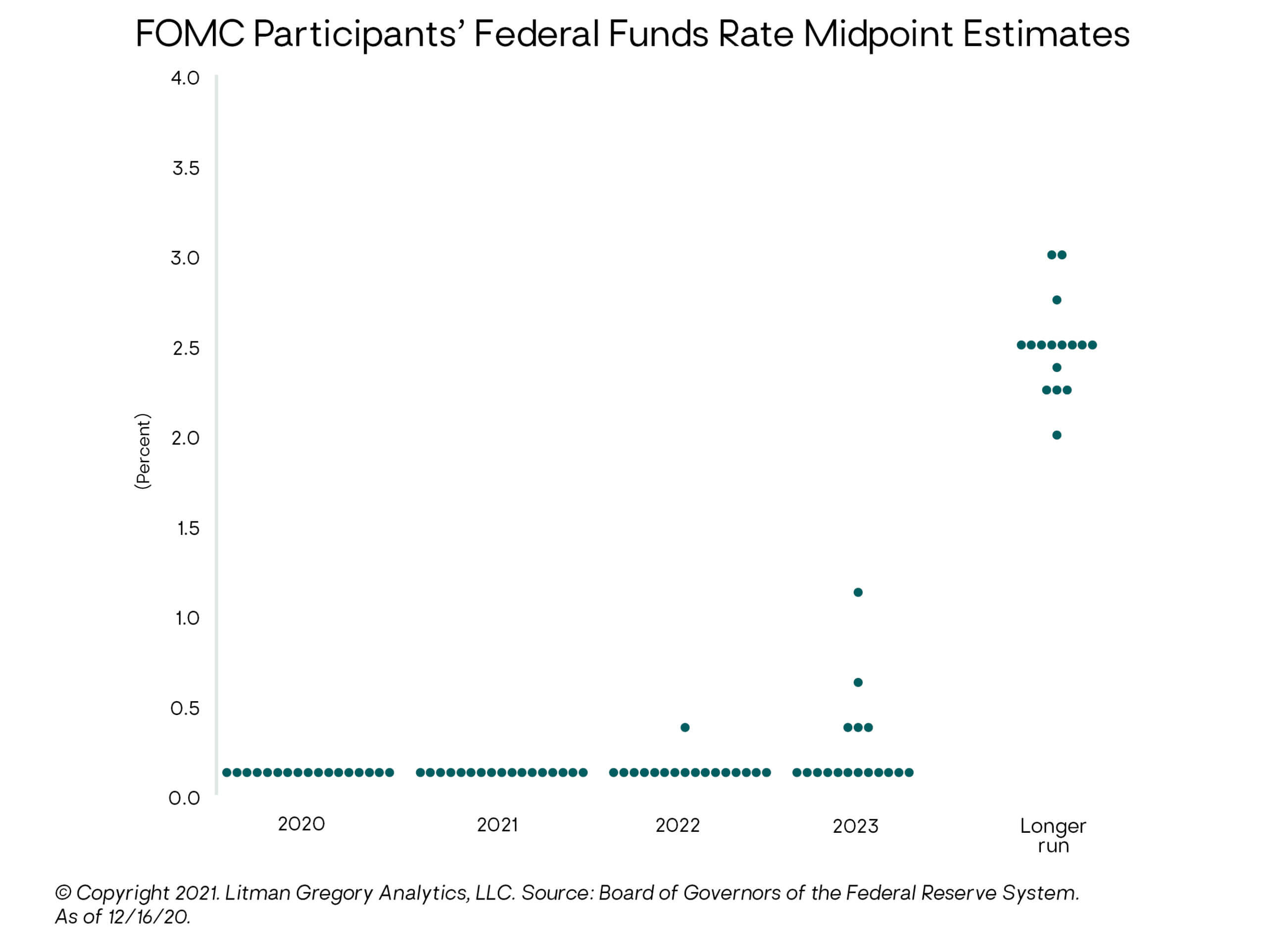

The recent rollout of the Fed’s “average inflation targeting” framework is further evidence of their apparent commitment to achieving “maximum employment” and core inflation “moderately above” their 2% long-term target before they start to raise interest rates. Currently, most Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participants don’t expect that to happen until at least 2024. Of course, that is subject to change, and the Fed’s track record of predicting even their own behavior is quite blemished. But barring an extreme inflationary shock, the Fed’s current stance is likely to sustain for at least the next year or two. The Fed is forecasting core inflation of 1.8% in 2021 and 1.9% in 2022.

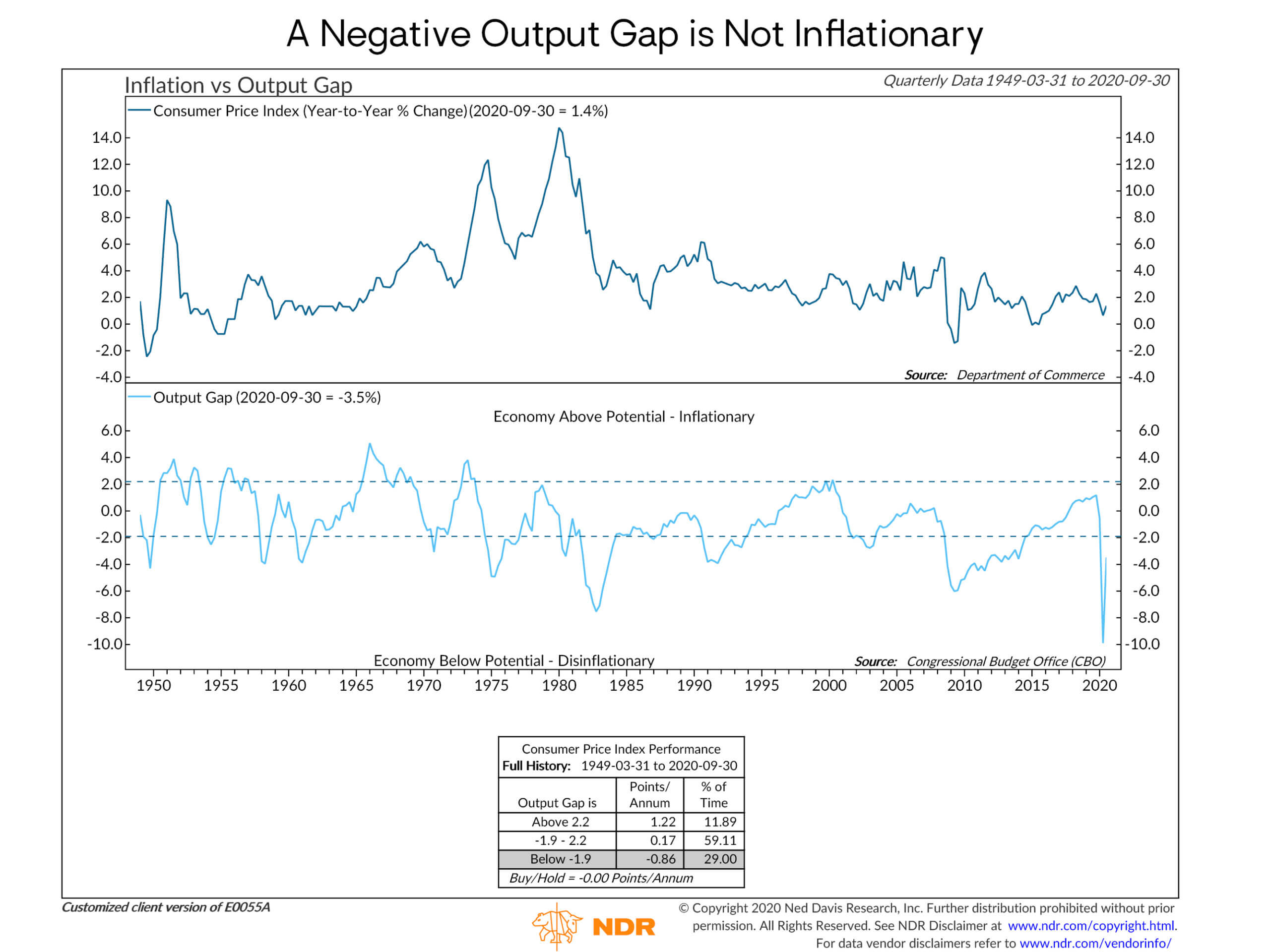

In 2021, inflation should get a boost from the economic recovery—and may temporarily rise above a 2% rate on a year-over-year basis compared to depressed 2020 price levels. But inflation is unlikely to move sustainably or significantly higher—again absent an external shock—as long as there remains high unemployment and excess economic capacity (the economy is still operating below its potential). The Fed is forecasting a 5.0% unemployment rate for 2021 and 4.2% in 2022.

So, short-term interest rates should remain near zero. Longer-term government bond yields may rise moderately as the pandemic (hopefully) recedes and investors start to price in a more normal economic recovery cycle. But, if it wants, the Fed has tools to contain yield increases farther out on the maturity spectrum (for example, it can start buying more intermediate- and longer-term bonds within its QE program).

Fiscal Policy

In 2021, fiscal policy is unlikely to be restrictive and could be stimulative depending on political outcomes, compromises, and the usual horse-trading. As we write this, it appears the Democrats have won the January 5 special runoffs for Georgia’s two Senate seats. This increases the odds of larger fiscal stimulus, possibly offset to some extent by corporate and individual tax increases. But even with Democrats in control of the Executive and Legislative branches, they likely still won’t get everything they want. There are many fiscally minded Democrats that will moderate the new administration’s proposals (especially on taxes). One would think politicians’ self-interest (not to mention the common interest) would prevail in that event and lead to other compromise packages.

With the above as a reasonable short-term (12-month) macroeconomic base case (and understanding that just because it’s reasonable doesn’t mean it will actually play out that way!) we’ll move on to what the implications might be for financial markets.

In a nutshell, an economy in the early stages of cyclical recovery, assisted by highly accommodative monetary policy, and, at worst, neutral fiscal policy, should provide a supportive backdrop for stocks and other “risk assets” over the course of the next year.

Market Outlook

Global Equities Outlook

In an environment in which the U.S. and global economies are in a synchronized early-cycle growth phase, corporate profits should be strong. Consensus estimates are for S&P 500 operating earnings-per-share growth of 38% in 2021, after a 23% drop in 2020. And monetary policy is loose, which should be fundamentally positive for risk assets such as stocks and “non-core” (lower-credit-quality) bonds.

But when investing one cannot just look at the fundamentals. The critical analysis is assessing the extent to which one’s fundamental outlook is already incorporated (or, in investment jargon, “discounted”) in current financial asset prices.

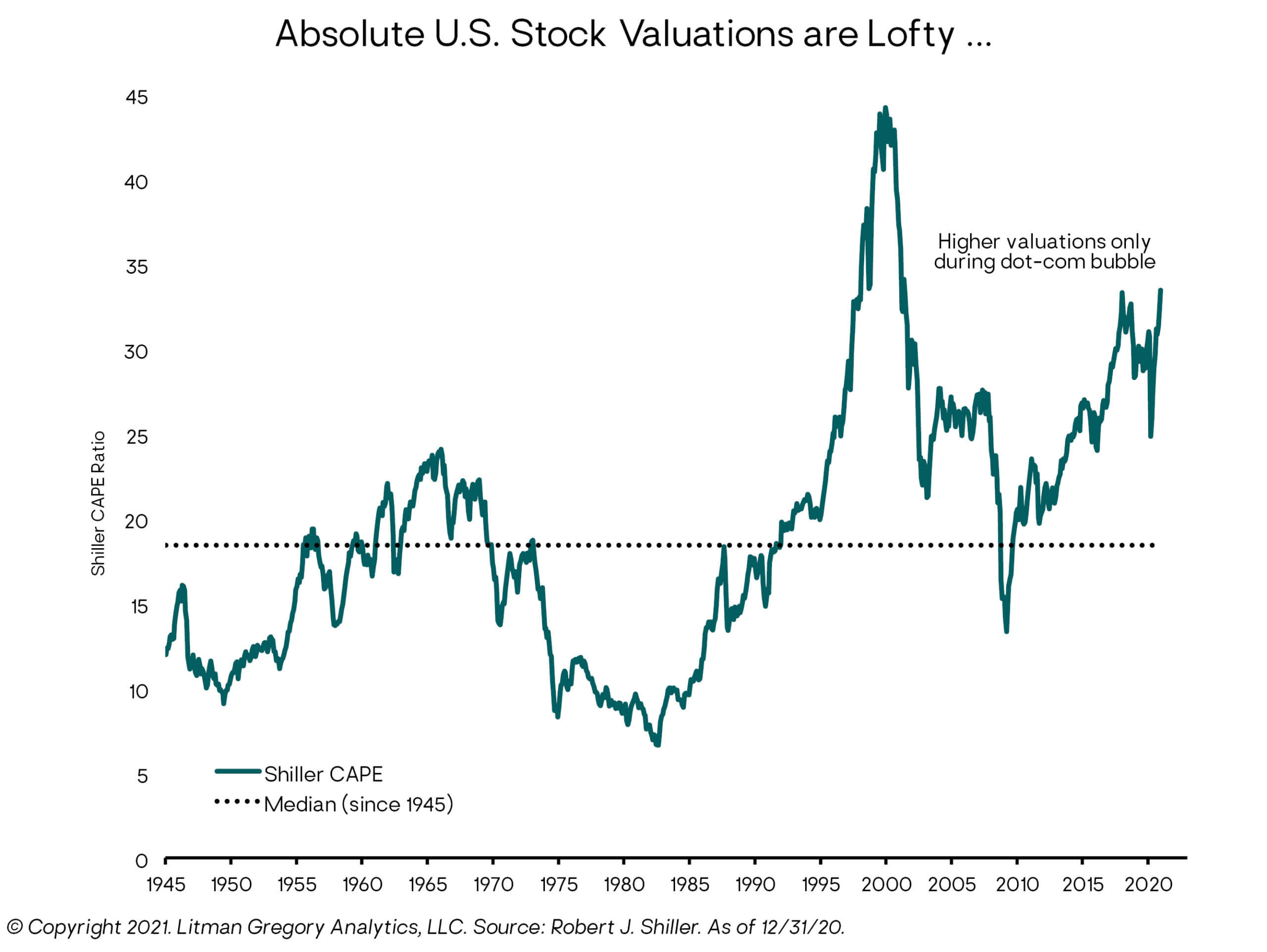

In other words: Valuation—the price one pays—also matters. And over the “medium term” (our tactical five-year analytical horizon), our base-case analysis indicates the U.S. stock market is overvalued on an absolute basis (compared to its underlying fundamentals or its normalized earnings power). Our base-case five-year expected annual return for the S&P 500 is in the very low single-digit percent range.

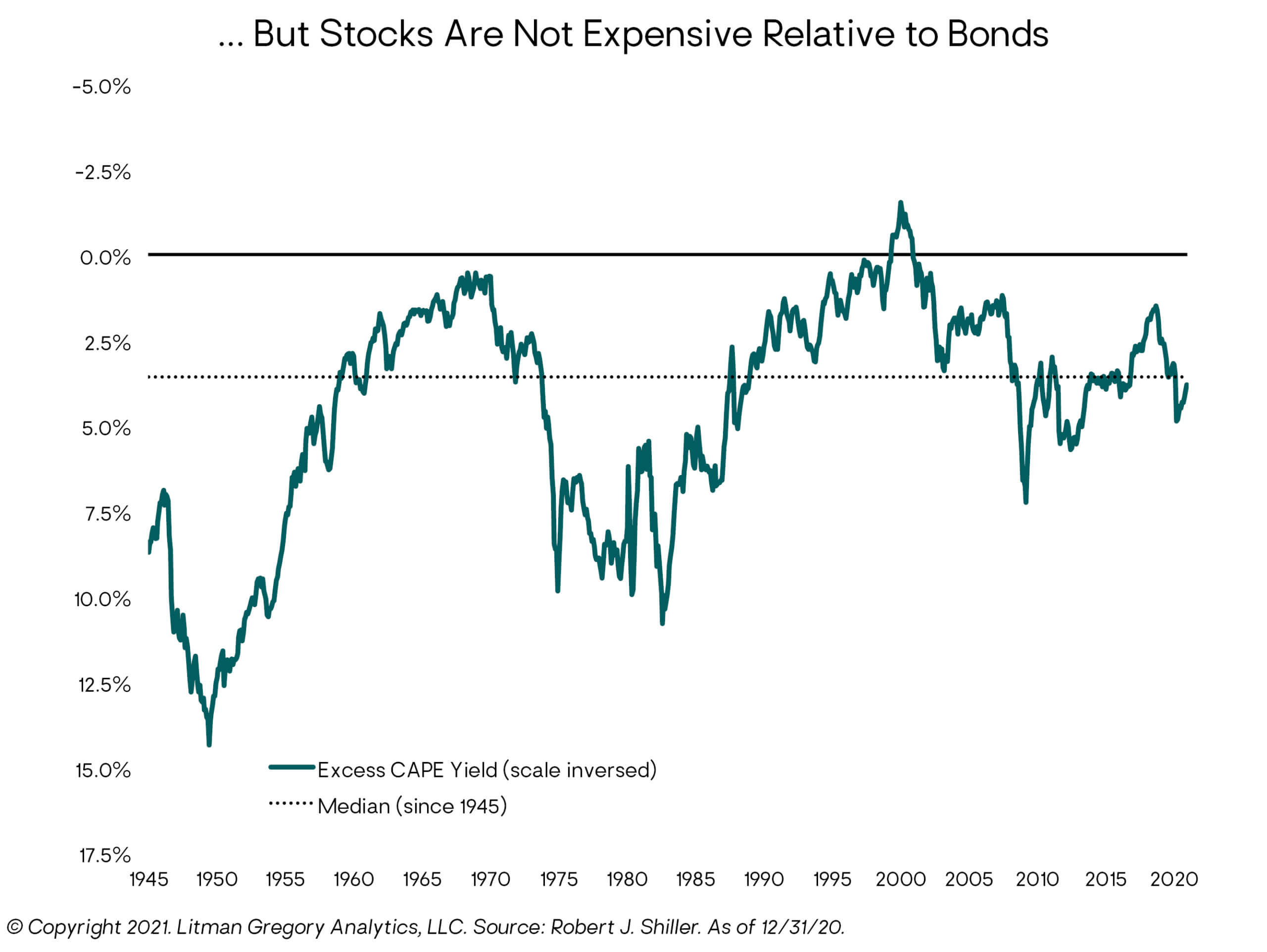

However, as we’ve also discussed in prior commentaries, in this environment of extremely low bond yields, U.S. stocks still look relatively attractive compared to core bonds or Treasury bonds. This relative valuation perspective has dominated market behavior for several years—memorialized in the acronym TINA (there is no alternative). Meaning, with core bond yields so low, investors have “no choice” but to move out on the risk spectrum and buy stocks and other riskier assets to try to meet their investment return and income objectives.

As long as bond yields remain very low and corporate earnings growth is meeting or exceeding expectations, U.S. stocks can continue to perform well or at least decently. High absolute valuations imply subpar medium-term absolute returns in our base case—and we see much better tactical opportunities in other markets—but they don’t mean a U.S. bear market is imminent.

Our research team is in the process of updating key assumptions in our base-case analysis of U.S. equity expected returns, given our evolving view that interest rates are likely to remain lower for longer and central bank policy is likely to remain very dovish even if or as global economic growth and corporate earnings cyclically recover. We expect to report on the results soon, but based on our preliminary work, we don’t expect to change our current portfolio positioning as a result of the updated assumptions. However, it will impact the S&P 500 levels at which we would add U.S. equity exposure in a future market selloff or reduce our equity exposure if valuations sharply expand.

Foreign equity markets should be even stronger beneficiaries of a global recovery, given their generally higher cyclical sensitivity to global growth—a trait that has hurt them throughout the generally lackluster economic period since the 2008 financial crisis. Plus, as we’ve highlighted for the past several years, they have significantly lower valuations compared to U.S. stocks.

So, we see potential for better-than-expected earnings growth and possibly also some increase in valuation multiples for stock markets outside the United States. Our base-case five-year expected returns for developed international and EM stocks are in the upper single digits. This is a substantial premium above U.S. stocks. As such, we remain overweight to EM stocks, where our conviction is highest, funded from an underweight to U.S. stocks.

Importantly, our tactical position in foreign versus U.S. stocks is based on our medium-term (five-year) analysis. But this positioning also aligns very well with the shorter-term macro outlook we’ve been describing.

In addition to favoring foreign over U.S. stocks in the near term, many of the above points also apply to the cyclical/value stocks vs. defensive/growth stocks debate. The former have been crushed, most recently by the pandemic, before that by the U.S.-China trade war, and, most broadly, by this extended period of low growth, low inflation, and very low interest rates that has strongly favored large-cap tech/growth stocks. But as the global economy recovers, these underperforming and out-of-favor stocks should show some life. Once the pandemic is perceived as under control and the economy is in a sustained upswing, we would expect “value” to have its day in the sun again, after an unprecedented 13-year run of massive underperformance. We’ve already seen this since the Pfizer vaccine announcement in November.

U.S. Dollar Outlook

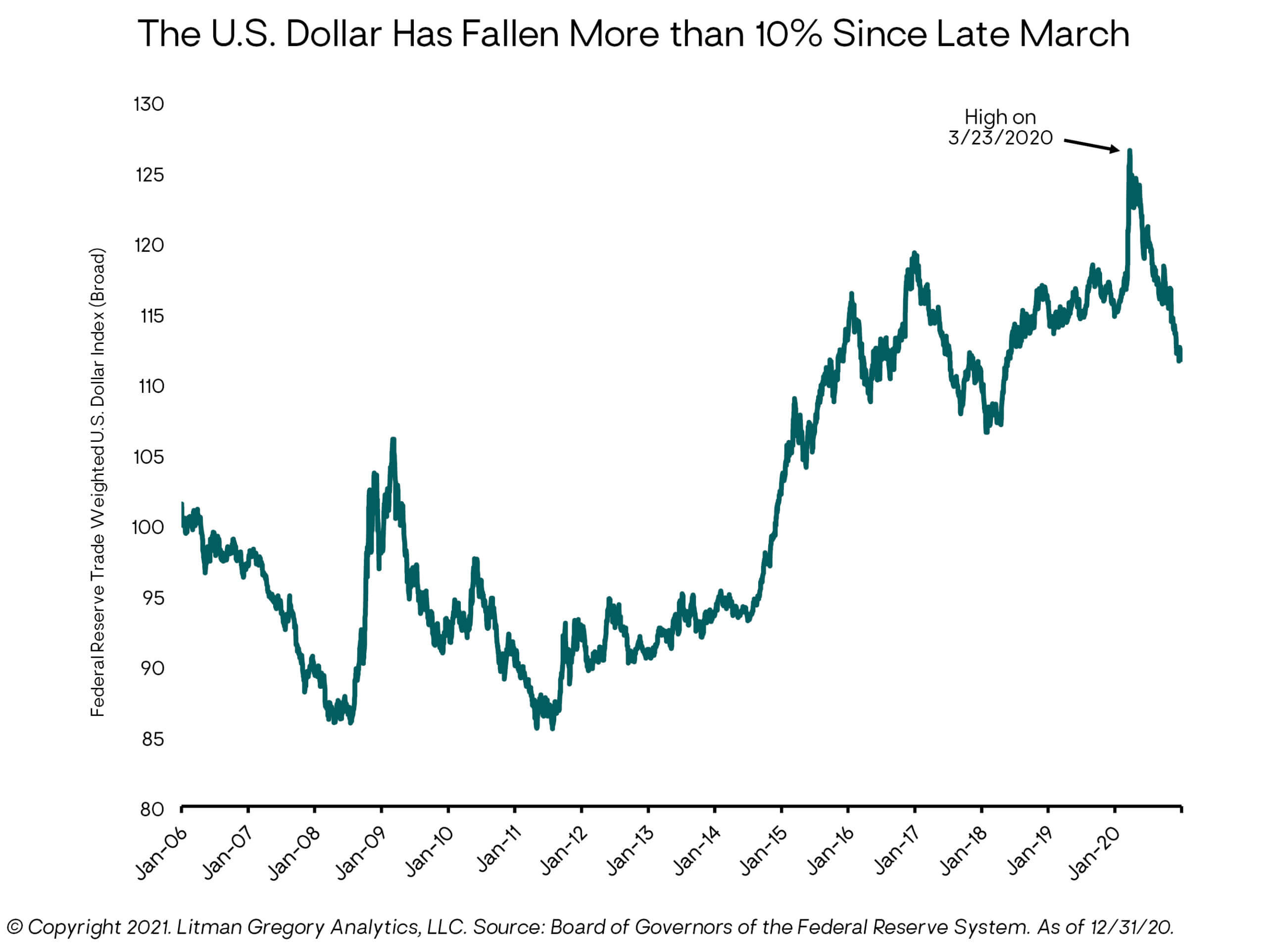

The direction of the U.S. dollar is another important variable for foreign markets and the global economy. When the dollar depreciates, it increases the return to dollar-based (unhedged) investors in foreign assets, and vice versa. A weakening dollar also eases global financial conditions and bolsters global economic growth by easing the cost of dollar-based debt for foreign borrowers. Emerging markets, in particular, have historically been beneficiaries of dollar weakening and looser financial conditions.

We are not in the business of predicting currency moves, but the dollar is typically viewed as a safe-haven (risk-off) currency. It tends to appreciate and depreciate in a broadly “counter-cyclical” fashion, meaning it tends to move in the opposite direction of the global business cycle. So, a rebound in the global economy in 2021 should be a negative for the dollar relative to other more pro-cyclical currencies in both international developed countries (like the euro) and emerging markets.

There are other dollar headwinds as well: (1) With the Fed rate cuts in 2020, U.S. bond yields are relatively less attractive than they were, so there is relatively less demand for U.S. dollars; (2) the dollar is expensive on a fundamental valuation basis; (3) a growing U.S. trade deficit implies downward pressure on the dollar; (4) the technical trend (momentum) has turned negative for the dollar and has further room to run in a self-reinforcing cycle; and (5) neither the Fed nor the U.S. government want a stronger dollar, as it has deflationary implications.

Fixed-Income Outlook

The outlook for fixed-income is relatively more certain (with a narrower range of potential outcomes) than for equities given the tight mathematical relationship between bond market yields and total returns. Given the 1.03% current yield for the core bond index, we have a high degree of confidence that core bonds’ five-year expected returns will be in the 1% ballpark. On an after-inflation basis—assuming roughly 2% inflation—their “real yield” is negative. So, from an absolute- and relative-return standpoint, core bonds are very unattractive (although there are opportunities for active management to do better than the index by investing in investment-grade bond sectors not included in the index, such as asset-backed securities).

However, core bonds still play a vital risk management role in our balanced portfolios. They provide “ballast,” or safe-haven protection and positive return potential in the event of a recessionary or deflationary shock. The pandemic was the most recent example. So, we maintain meaningful exposure to core bonds with higher allocations in our more conservative/risk-sensitive portfolios. However, given the very strong rally in Treasuries (with the 10-year yield below 1%), our tactical allocation to intermediate-term Treasury bonds is under review by our research team.

We also believe it is important in this environment to diversify one’s fixed-income exposure well beyond core bonds. With current core bond yields so low, they are particularly susceptible to capital losses from rising interest rates. And as noted above, we’d expect to see some increase in medium- to longer-term interest rates if the global and U.S. economies rebound in 2021. The Fed certainly doesn’t want a sharp rise in longer-term rates—the economy likely couldn’t handle it—but it should be fine with a moderate and gradual rise if it is in response to a stronger economic outlook from investors.

Our positions in flexible, multisector, credit-oriented bond funds and floating-rate loan funds should outperform core bonds in this scenario, benefiting from both their higher yields as well as potential price appreciation/yield-spread tightening (a decline in the extra yield investors require as compensation for default risk expressed by rising bond prices). Again, we have already been seeing this happen in the second half of 2020.

Alternatives Outlook

With U.S. stocks and core bonds likely to deliver sub-par returns over the medium term, our allocations to marketable alternative strategies (multi-strategy fund and trend-following managed futures) have good potential to improve overall portfolio returns as well as provide valuable diversification benefits across a wide range of macro scenarios.

The Risks to Our Outlook

While the macroeconomic and investment backdrop is positive, there are risks to our outlook, as always. Some are very-near-term market risks (over the next few months), which mirror the very-near-term macro/pandemic risks we discussed above. Others are more relevant looking out over our tactical five-year medium-term horizon.

The Very-Near-Term Market Risks

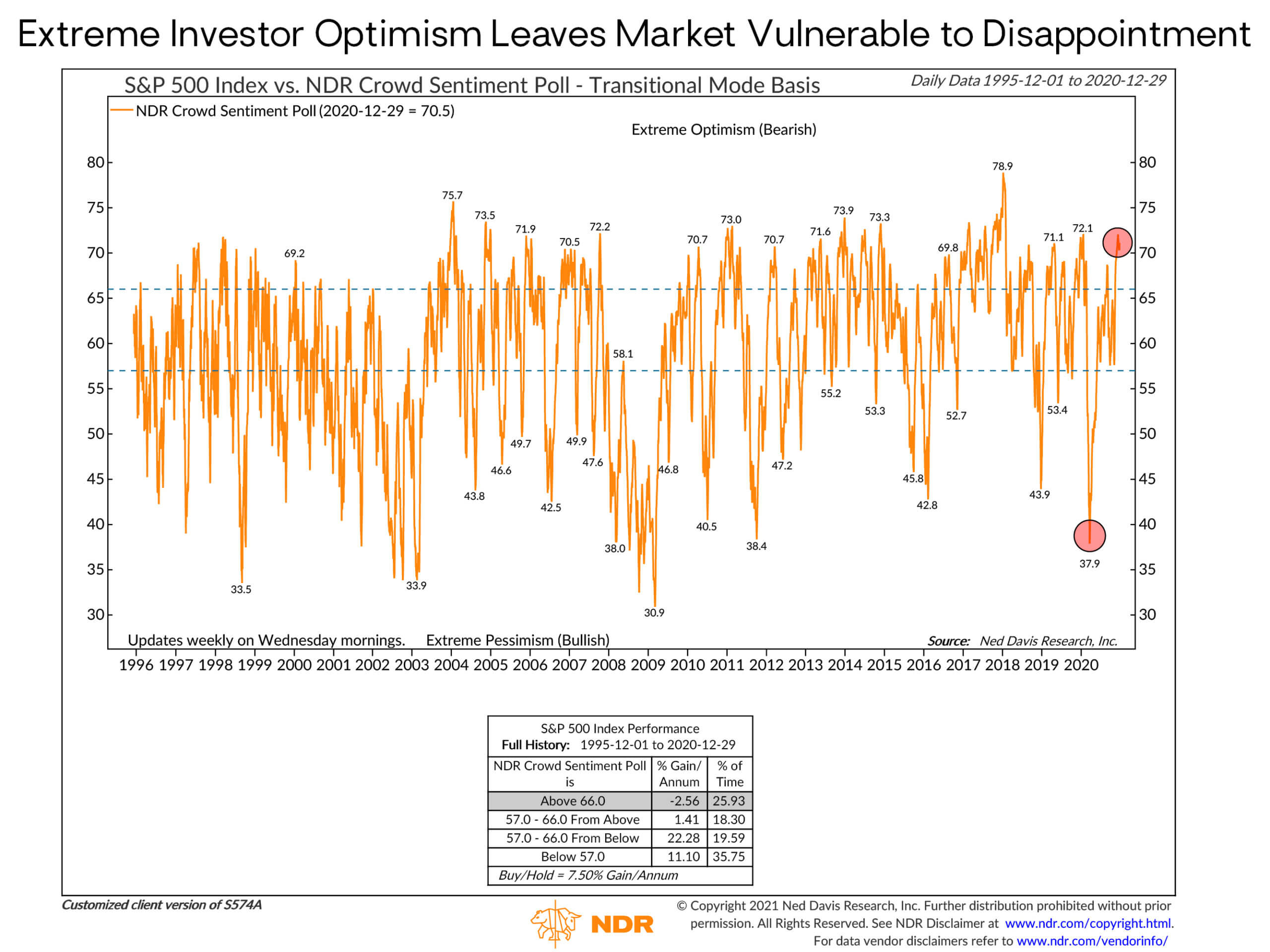

After the U.S. stock market’s incredible rebound since late March—with the S&P 500 up 70% and the Nasdaq up 89%—market sentiment (investors’ collective willingness to take risk) is very bullish and very optimistic. When sentiment reaches such extremes, it can be a contrary indicator for the market in the very near term. As an example, the Ned Davis Research chart below shows a composite of sentiment indicators. It is currently in the “Extreme Optimism” zone, where subsequent market index returns have historically been negative on average. In contrast, crowd sentiment hit its most pessimistic reading in 11 years when the market plunged in late March. This set the stage for a powerful market rally given the catalyst of an overwhelming monetary and fiscal policy response.

Intuitively, extreme investor optimism implies a lot of good news is already priced into the market. This leaves the market particularly vulnerable to any type of fundamental disappointment, whether on the economic or corporate earnings fronts, the pandemic/vaccine front, or the political/geopolitical front.

Of course, beyond these specific short-term risks, equity investors should always be prepared for market volatility. It comes with the territory and is the price paid to earn the higher expected returns from owning stocks over the longer term. Given the positive bigger-picture macro environment and market outlook, we’d very likely view any near-term market declines as temporary hiccups.

Looking beyond these very-near-term risks to the full year ahead, we are cautiously optimistic about the potential returns across a range of financial assets. Our caution stems from the inherent uncertainty in any economic or investment forecast, the inevitability of surprises, and the necessity to manage for a wide range of risks in our client portfolios.

Two Key Medium-Term Market Risks

The medium-term risks are numerous; some are known and some are unknown. We will highlight two here: inflation and China.

Inflation

Ever since the Fed embarked on QE and zero interest rate policy in 2008, many prominent investors, strategists, and economists have been warning of an imminent inflationary spiral. They have been dead wrong. But with even more extreme Fed accommodation and money supply growth in 2020, the prospect for further debt-financed (monetized) government spending still to come, and a post-pandemic global economic recovery eventually driving the economy to full employment/full capacity, at some point over the next five years we see increased inflation risk.

We believe central banks will be in no hurry to raise interest rates, as they’ve repeatedly stressed. They will no longer act preemptively to contain anticipated inflation. But eventually, even with average inflation targeting the Fed will start raising rates if and as we get a more normal, late-stage, overheating economic cycle.

In past cycles, besides an external shock, Fed tightening has typically been the weapon that has killed economic expansions and triggered equity bear markets. It’s a reasonable bet to expect that to happen again this cycle. Moreover, given the huge and growing mountain of government debt, rising Treasury rates will also start to impose a large debt servicing burden on the economy.

A period of sharply higher inflation and rising interest rates will obviously be bad for core bond and nominal Treasury returns, although it will set up subsequent bond investments with higher yields.

High inflation is also bad for stocks, especially those with high price-to-earnings ratios (P/E multiples) as they will no longer get a valuation boost from exceptionally low rates. The reverse will likely be true and P/E multiples will compress. Once valuations reset and inflation stabilizes, stocks can perform well. So, over the long term they have been an excellent inflation hedge. But they are likely to take an initial hit if inflation accelerates above say 2.5% to 3%.

As a base case, it looks like at least a few years until the stage will be set for Fed tightening. The Fed itself doesn’t expect to start raising rates until at least 2024. But a lot can happen between now and then to cause them to change their collective mind.

Unexpectedly high inflation could emerge if demand strongly outstrips supply. Rising demand could stem from consumer and business “animal spirits” being unleashed after the pandemic, further accelerated by aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus. Meanwhile, the supply side could be constrained by the “regionalization” of economic activity—a retreat in the globalization of the last three decades as manufacturing and global supply chains are re-engineered closer to home at additional cost.

If an inflationary spiral took hold, it would take strong Fed medicine (raising rates) to break it, as we saw in the early 1980s. A global “run on the dollar”—extreme dollar depreciation or debasement—would also likely force the Fed to raise rates to protect the reserve currency. We view this as a very low probability scenario—at least any time soon—but the probability isn’t zero.

Between our actively managed, flexible fixed-income and floating-rate loan funds, our alternative strategies, and our global equity exposure (diversified across U.S., international, EM, value, cyclical, and growth stocks), we are confident our balanced portfolios can perform well in the event of unexpected inflation. Many clients also have meaningful exposure to private real estate funds, which should hold up in an inflationary period. We also have other inflation-sensitive assets in our investment opportunity set (such as TIPs and commodity-related funds) should we see the need for additional inflation protection.

China

Given China’s outsized influence within the emerging markets (not to mention the world at large), we are very focused on the risks it presents, in addition to the investment opportunities.

China has handled the pandemic relatively well and recovered from it the fastest, among the major economies at least. In October, the IMF estimated China would be the only country in the world with positive economic growth in 2020. China has also been among the best-performing stock markets in the world, up almost 30% for the year, while its currency, the yuan, has appreciated more than 6% versus the U.S. dollar since the end of May. Investors are acknowledging the relative growth differentials between the U.S. and Chinese economies.

There has also been increased global demand for China’s bonds. China’s 10-year government bond yield is around 3.2% and appears attractive to yield seekers in an era of very low to negative government bond yields in much of the developed world. Given China’s economic recovery has been faster than expected, China’s government has indicated it will be looking to normalize monetary policy next year (it is relatively hawkish). In addition, China is increasing regulatory scrutiny on some of its large tech companies that have performed well. Given these shorter-term headwinds, it would not be unreasonable to think that the Chinese stock market takes a breather relative to the rest of the emerging markets and some other developed markets, such as in Europe.

Medium to longer term, we remain bullish on China and EM stocks in general. For EM stocks, we believe our base-case valuation and earnings assumptions are relatively conservative and think there is a good possibility that we will be surprised on the upside.

We think the trade and tech war–related issues will likely remain a headwind for China and the emerging markets over the medium to longer term. If anything, a Biden administration may end up putting more coordinated pressure on China. In this respect, China’s increasing focus on domestic consumption–led growth while strengthening intra-Asia trade and seeking new agreements (such as an investment agreement with the European Union currently underway) could help offset U.S.-China trade war–related headwinds.

Importantly, if the trade war between the United States and China accelerates the aforementioned economic regionalization, especially given the growing importance of China, it becomes even more important for investors to diversify across global equities and not be very U.S.-centric. We think we are in the early stages of this rebalancing in global investor portfolios as the current relatively low allocations to EM stocks and recent capital flows data suggest.

Closing Thoughts

We incorporate a wide range of potential outcomes in our scenario analysis and portfolio construction. For 2021, we think a reasonable base case is that the widespread distribution of vaccines (along with testing, treatment, and other public health responses) is effective in bringing the pandemic under control. This will enable the U.S. and global economies to stage a reasonably robust growth recovery off a still-depressed base. The recovery will be supported by ongoing highly accommodative central bank monetary policy, keeping interest rates low. And there will be enough fiscal aid to households and businesses to at least bridge the economic chasm while the pandemic rages earlier in the year.

This macro backdrop should be positive for global equity returns—particularly for undervalued international and EM stock markets and other beaten-down cyclically sensitive assets. Credit-oriented fixed-income strategies and alternative strategies should also outperform core bonds.

We admit this seems to be the consensus view for 2021 as well. That makes us a little wary; the consensus is often wrong. But there is no payoff to being contrarian just for contrarian’s sake. From a portfolio performance perspective, we’d be very pleased to see our formerly contrarian views on foreign stocks vs. U.S. stocks and value vs. growth become the consensus in 2021 and beyond. Our analyses of these asset classes suggest there is still a lot of room for more gains (and for the consensus to turn more bullish on them), even with their rebound in the latter part of 2020.

Our portfolios are well positioned if the consensus view plays out in 2021. However, our positioning is based not on one-year market predictions or economic forecasts that are notoriously difficult to consistently get right but on our five-year, multi-scenario, expected-return framework in conjunction with our shorter-term risk assessment. That said, it is encouraging to see such strong alignment between our medium-term baseline scenario and the shorter-term view.

If we have learned anything from financial market history, it is that one should expect the unexpected; expect to be surprised. There is no certainty, and much can go wrong in any given year. Much can also go right, such as the incredibly fast development of COVID-19 vaccines and the overwhelming bipartisan policy response to the pandemic early in the year (unfortunately, this bipartisan spirit didn’t last long).

Right now, we believe the consensus view is a very reasonable shorter-term base case. Nonetheless, and as always, our portfolios remain diversified across a range of assets and investments that should provide balance and resilience in the event this sanguine outlook doesn’t play out. We are prepared to respond prudently, thoughtfully, and opportunistically as unexpected events unfold, just as we did in March of 2020.

We appreciate your confidence and trust in Litman Gregory. We sincerely wish everyone a healthier, happier, peaceful, and prosperous New Year.

—Litman Gregory Investment Team (1/7/20)