Research Update: Trend Following with Managed Futures

We have long been proponents of managed futures strategies for their powerful diversification benefit, and more specifically for their ability to deliver positive contributions to a portfolio at times when nothing else seems to be working. Understanding how trend-following managed futures’ strategies work, and how they take advantage of market and investment trends, is important for setting expectations for what is behind their performance. The evidence of the long-term value that managed futures bring to a balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds is compelling, however there can be shorter periods where sharp see-saw patterns can lead to disappointing returns. But in a year like 2022 that saw significant declines for both stocks and bonds, managed futures experienced large gains (see table below) and were one of the only asset classes to provide meaningful downside protection.

What Are Managed Futures and Trend-Following Strategies?

Managed futures strategies are employed by investment managers who are registered with the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC’) as Commodity Trading Advisors (CTAs)– a designation that establishes proficiency requirements and oversight for those advising on and trading in derivatives including futures contracts.

Managed futures strategies can be market-neutral, where they seek to identify securities mispricings and can play spreads or use arbitrage to capitalize on them, or trend following, where they can use technical or fundamental data to inform buying or shorting futures to capture either rising or falling price trends in various markets such as stocks, bonds, commodities and currencies. Our due diligence work has led us to favor quantitatively driven trend-following managed futures strategies, for several reasons. While most strategies we look at bring the benefit of very low correlation to core asset classes like stocks and bonds, we have more confidence in the trend-following strategies because of the ongoing persistence of trends which are a primary driver of absolute returns for these quantitative approaches. Strategies that use fundamental analysis can be more dependent on qualitative judgments and in theory this can reduce the reliability of the diversification benefit during periods when it’s needed most.

But trend following strategies require the existence of trends in order to work. Periods with weak or choppy trends and poor relative performance from trend following managed futures strategies inevitably lead some to question whether fundamental changes to investor behaviors – perhaps driven by information technology, automated trading, artificial intelligence, etc. – mean the kinds of trends we’ve seen in the past are unlikely to occur in the future. While we acknowledge and observe that there are periods where trends are weaker, we see no evidence suggesting that going forward we are unlikely to continue to see the kinds of trends that managed futures strategies can take advantage of to produce positive returns for investors.

A very simple way to think about the persistence of trends over time in this investment context is well described by The Hedge Fund Journal1, which writes:

…many managed futures strategies profit from sustained capital flows in financial markets. These flows occur as a particular market moves from a state of imbalance toward a new equilibrium. Capital flows can take the form of rising markets as well as falling markets…”

What that description captures nicely is the point that trends aren’t just seemingly random ebbs and flows that may or may not persist for any particular duration. They are deeper rooted and connect to innate investment behavior in which it takes time for “water to find its own level” as underlying fundamentals change and are eventually reflected in pricing.

What We Look for in Managed Futures Strategies

The sometimes black-box nature of the quant approaches adds to the challenge of identifying managers likely to deliver the complementary performance we seek from owning managed futures. While managers are not likely to share exact details on the inner workings of their proprietary models, our research on the strategies we have selected has allowed us to gain a strong sense of their overall approach, including:

- The use of shorter-term, mid-term or longer-term trend signals

- The degree to which these can dynamically change

- How various signals are weighted (e.g., always constant versus overweighting stronger signals)

- Which markets are traded and how they weight various markets and contracts

- Their volatility target and whether it can change

- How allocations to other strategies involving factors like carry or mean reversion are determined (if any are used, as these are much less common than trend following and have different return profiles)

In assessing performance, we look at attribution to understand how various aspects of the strategy have contributed to performance during historically relevant periods. The more models they use and markets they trade the more difficult it can be to accurately determine attribution, especially during periods with weaker trends. However, during periods of stronger performance for trend followers, like 2008, 2014 and 2022, attribution becomes more clear and helps us set performance expectations in different market environments with somewhat more confidence.

That said, just as with equity managers, some managed futures approaches will work better during certain market environments than others. Given that we don’t believe it’s realistic to predict those environments over shorter periods, we want manager diversification in our managed futures allocation. The attributes we look for in managers we use in our portfolios include:

- Intellectual honesty and humility about the inherent limitations of creating, evaluating and adapting models

- Reasonable level of transparency around model specifications and portfolio construction

- Sensible and clear approach to risk management

- Balance of trying to improve the process over time (in terms of models, portfolio management, trading costs, etc.) without over-optimizing for recent performance/market environment

- Good historical performance, obviously, but performance that makes sense in the context of the manager’s investment style

- There should be periods of poor performance and the manager should be open in explaining them and, again, it should make sense in the context of their investment process/style

- Strong firm-level infrastructure and operational capabilities

Our due diligence work on managers and the strategies they employ helps us create a diversified allocation to managed futures where in aggregate we have confidence in the benefit it brings to the portfolios we manage — namely that they improve the risk-return profile through their strong diversification benefit.

Diversification Benefits of Managed Futures

Managed futures are regarded as an ”alternative” asset class, in that their role is to provide diversification and mitigate the volatility and downside risk of a portfolio primarily comprised of more traditional investments, such as stocks and bonds. And the compelling evidence that managed futures improve the long-term risk return profile of an otherwise-diversified portfolio convinced us a number of years ago to include managed futures in our standard client portfolios. We will walk through some of the more compelling evidence by looking at portfolios with and without managed futures in terms of their long-term returns, volatility and drawdowns in bad market environments.

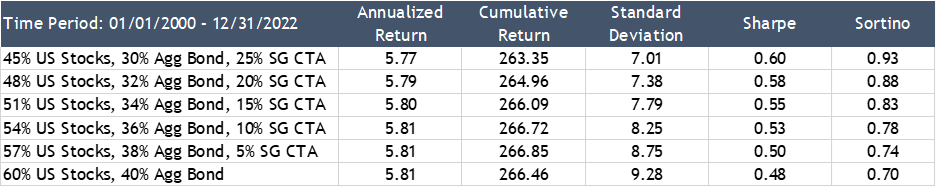

If you look at adding managed futures pro rata to a 60/40 portfolio (60% stocks/40% bonds) at various allocation levels, starting with 5% managed futures and increasing at 5 percentage point increments up to 25% managed futures (1/1/2000 through 9/30/2022, rebalancing annually), each additional notch higher in the managed futures allocation modestly increases returns since inception, and significantly decreases the portfolio’s standard deviation (which measures the volatility of returns), thus also materially increasing risk-adjusted return measures (shown as the Sharpe Ratio and Sortino Ratio).i

See below for important composite disclosure.2

These measures are impressive, but — to mangle an investment adage — you can’t eat Sharpe Ratio. The investor experience is usually driven much more by absolute numbers, positive or negative. Looking at the reduction in drawdowns in various crisis periods may be the most valuable way to understand the real-life implications of a managed futures allocation.

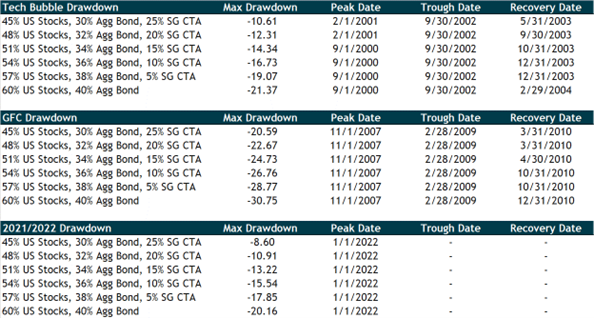

Below we show the reduction in drawdowns of a 60/40 portfolio with the managed futures combinations, using as examples the bear market following the Tech Bubble (2000-02); the Global Financial Crisis bear market (2007-09); and the current inflation-/interest-rate- driven bear market. Seeing historical data showing a benefit probably has some resonance, but there’s nothing quite the same as actually living through a bear market like the current one to reinforce the power of diversifying strategies.

Once again, the numbers are impressive. Even a small 5% allocation to managed futures would have saved you about 2.3 percentage points of performance this year – reducing a loss of 20.2% to 17.9%. A 10% allocation would have come close to cutting losses by a quarter.ii

How We Allocate to Managed Futures

The answer doesn’t come from looking at an asset allocation optimizer. If the goal is increasing risk-adjusted returns, an optimizer would tell you to allocate more than most investors are comfortable with, typically in the range of one-third of the portfolioiii with some variation higher or lower depending on the measurement period. This is one case where the decision should clearly be based on more than numbers.

A practical constraint on sizing allocations to highly diversifying strategies like managed futures is how much of a portfolio we are comfortable holding in an unconventional strategy that may experience extended periods of underperformance relative to other portfolio investments. This can be particularly challenging during periods when traditional stocks and bonds are doing well while managed futures are struggling.

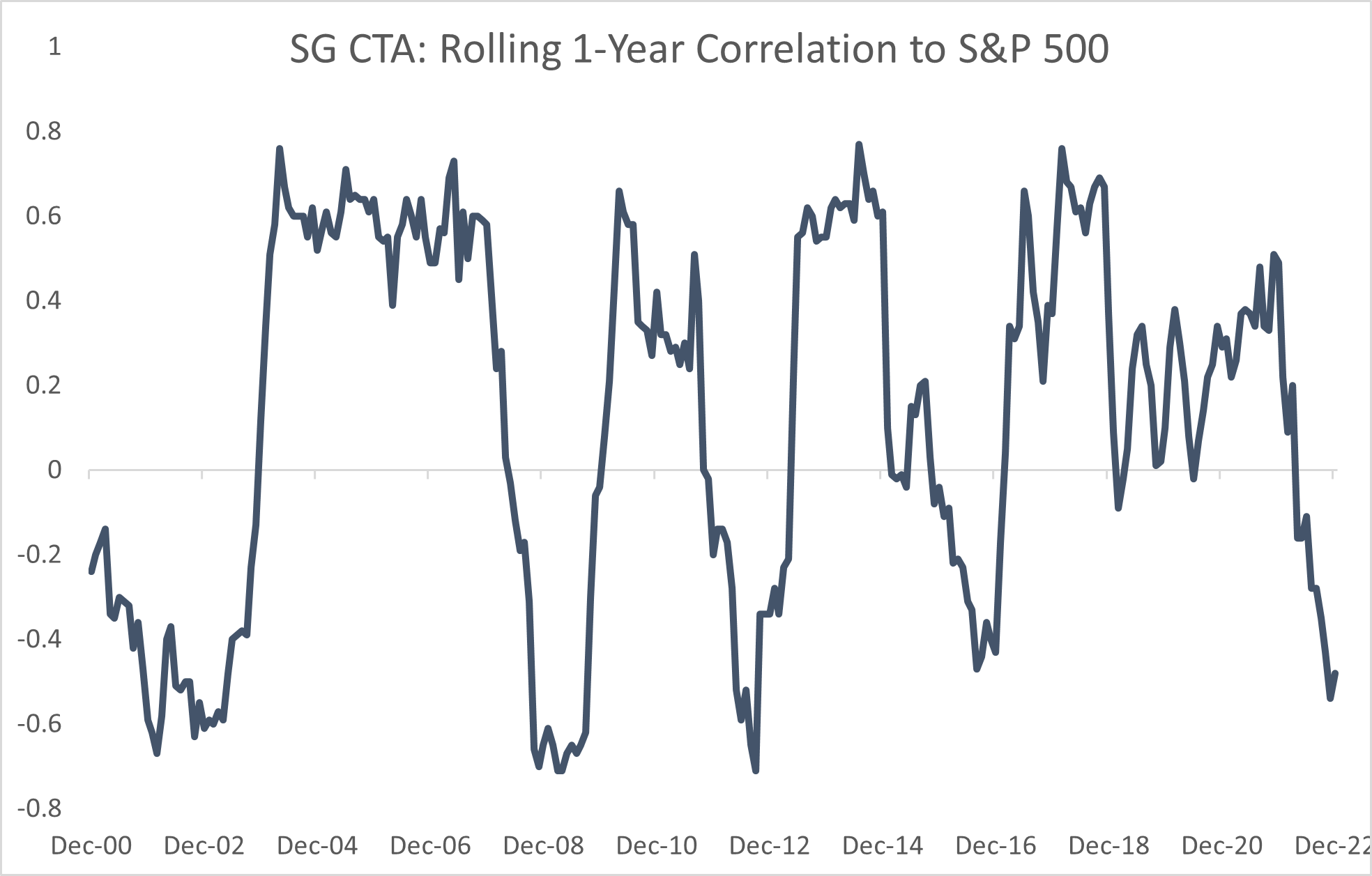

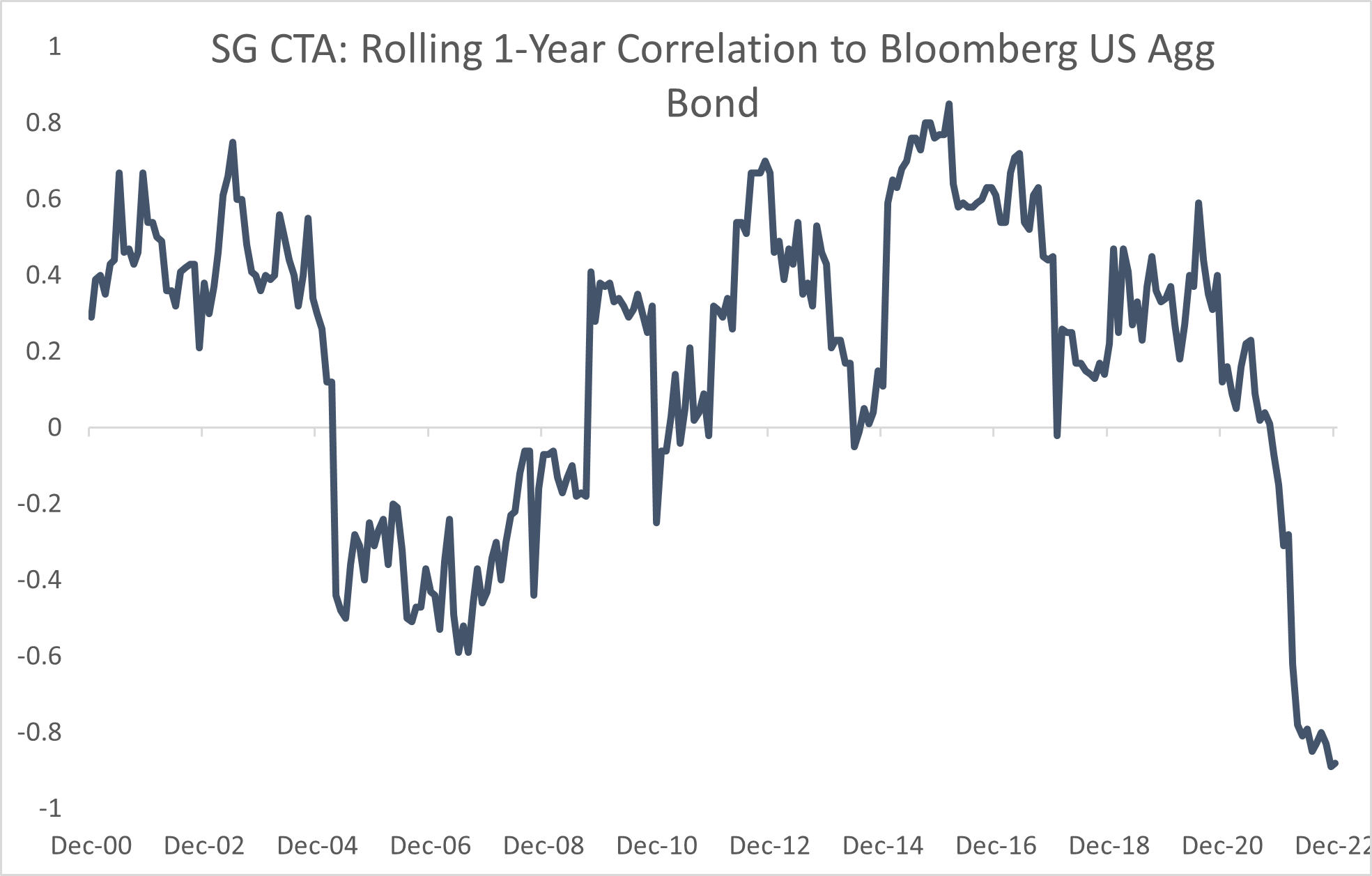

Why would an optimizer tell you to invest so much in managed futures? Simply put, because the strategy (as measured by the SG CTA Index) has generated similar long-term returns to a 60/40 portfolioiv, but with essentially zero long-term correlation to both stocks and bonds: specifically, -0.09 correlation to the S&P 500 Index from January 2000 through September 2022, and 0.08 correlation to the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Index (using monthly returns). Rolling 12-month correlations range between about -0.8 and +0.8 for both, with the potential for dramatic shifts over short timeframes. This makes intuitive sense given the potential for managed futures to be long or short any asset class. The combination of long-term positive expected returns with no correlation (and a propensity to perform well during market dislocations) we feel makes the strategy an incredibly valuable addition to a portfolio.

Source: Morningstar Direct as of 12/31/2022

Source: Morningstar Direct as of 12/31/2022

How should you fund a managed futures allocation?

Because managed futures have essentially no long-term correlation to anything, it makes sense to fund them pro rata from an existing allocation. The existing allocation has presumably been balanced for the investor’s return goals and risk tolerance based on the performance and correlation characteristics of its underlying components. Funding pro rata from these sources should preserve the expected return profile of the portfolio’s core, while adding the diversification benefits and (likely) crisis alpha of managed futures.

A reasonable case could also be made to fund an allocation more than pro rata from bonds, given stocks outperform bonds over long time horizons, and managed futures tend to perform well during extended stock market weakness (i.e., periods of weeks to months, not days to weeks). The “optimal” allocation depends on what is being optimized (risk-adjusted returns, expected maximum total return, etc.).

Opportunity costs factor into our calculus, particularly as an allocation becomes larger. To pick an extreme (and unrealistic) example for effect, if a managed futures allocation was funded entirely from equities beginning in 2015, the opportunity cost of that decision would have been huge over the next five years, as managed futures were essentially flat cumulatively, while the S&P 500 was up over 70% and a 60/40 portfolio was up almost 50%. One could of course find counterexamples, but the point is simply that the further one moves away from pro rata funding, the more it becomes an active “bet” against existing asset allocation, and the greater the chance of an extreme outcome that could derail an otherwise successful investment plan by potentially leading an investor to throw in the towel.

Summary

By virtue of their almost total lack of long-term correlation to other asset classes, combined with their ability to generate a modest long-term absolute return, trend following managed futures are a powerful diversifier to broader portfolios that include a traditional mix of stocks and bonds. They generally improve risk-adjusted returns and have provided downside protection during periods when stocks and bonds experienced large downturns. An added benefit in today’s economic environment is that historically managed futures have also been an effective inflation hedge during periods of elevated inflation.

But managed futures are complicated, in more ways than one. The trend following strategies used and the asset class itself can be difficult to understand and that can impact investors’ comfort. We hope the information we presented here helps to demystify this space and explain the fundamental aspects of what these investment strategies do and how they work.

Beyond the complexity, managed futures can sometimes be frustrating to own given their tendency to generate lower absolute returns relative to stocks and bonds during extended periods when those assets classes are performing well. This was the case for a lengthy stretch prior to 2022, and some investors found it difficult to stick with their allocation to managed futures. Now, after a difficult year for traditional stock and bond markets, and where managed futures had very strong absolute and even stronger relative performance, it is a good time to remember that it may be necessary to be patient in order to gain the diversification and downside mitigation benefits that managed futures can bring over the long term.