Research Update: Our Views on Inflation

As mentioned in our first quarter commentary, investors have been concerned about inflation. But while year-over-year consumer price index (CPI) inflation will most likely rise in the coming months, we agree with the Federal Reserve that the rise is likely to be transitory. We see an economy reflating as it recovers from a recession, not one on the edge of a hyperinflationary spiral. We have already positioned our portfolios to offer some inflation protection. But if we see the need to further hedge against inflation, we have additional options, each of which comes with tradeoffs.

Why Aren’t We Concerned About Inflation Near Term?

Base Effects

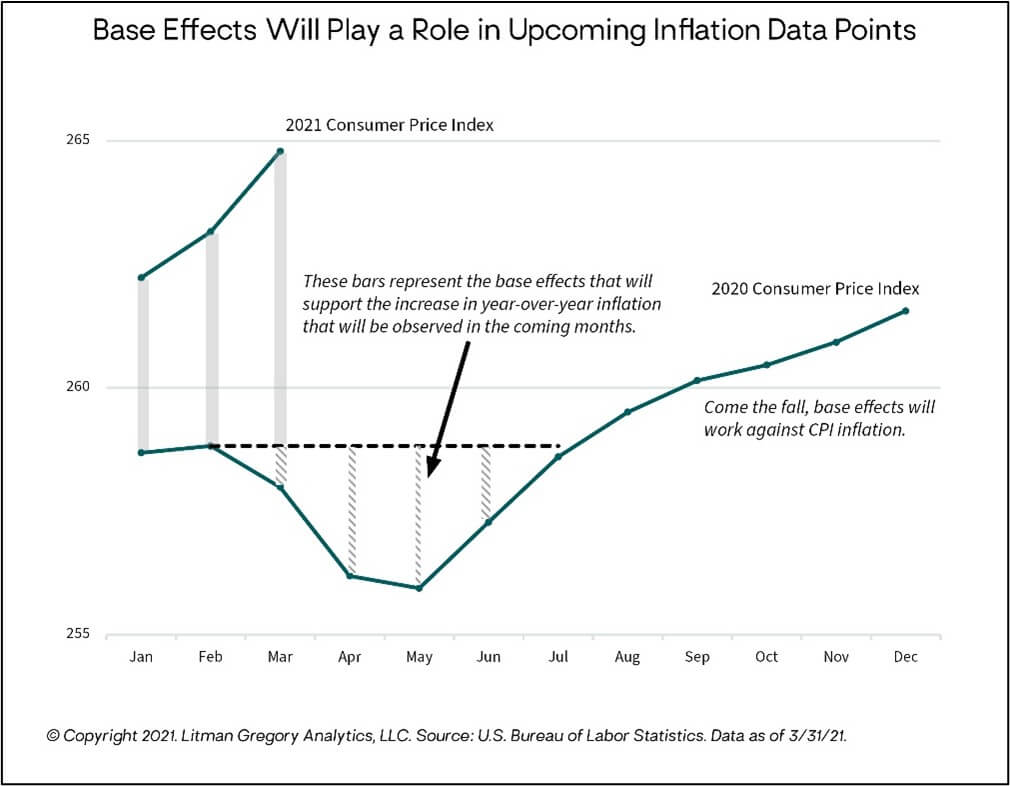

We believe that the so-called base effects will be a material driver of an upcoming rise in inflation. To explain what this means, consider that a year ago, in April 2020, the economy was approaching a nadir in economic activity due to the worldwide lockdown. The CPI dropped 0.7% during the month—its largest month-to-month decline since 1950 (outside the 2008 financial crisis). Now 12 months later, a one-year difference will be comparing today’s price level to a very low point, so in the near term, year-over-year changes will look larger. We’ve seen recently that CPI inflation can spike in very short-term periods, like it did in April, and we know forecasts could be well above 3.5% annualized in the coming months. But we believe a significant part of that increase comes from prices having rebounded after a great decline. The chart above tries to visualize this effect.

The chart further shows that after May 2020 the price level started recovering sharply. Thus, the base effects will eventually reverse and, starting later this year, even start working against a CPI increase.

Price Inflation

All this isn’t to say the entire coming CPI increase will be due to base effects. There have been reports of higher prices throughout the economy: lumber, corn, copper, semiconductors, home values, and rental cars, to name a few. Some of these are showing up in a surge in producer prices, a gauge of which recently had its largest 12-month gain in nearly a decade. Part of the rise in producer prices can be attributed to ongoing bottlenecks and supply chain issues. Many economists believe these will prove to be temporary consequences of the recent rapid recovery in demand. It remains to be seen whether companies will pass some of these higher costs off onto customers, which could lead to sustained inflation that would be worrisome.

Take for example what we saw in 2011, when the Producer Price Index (PPI) for commodities was rising at an 11% clip: Headline inflation rose above the Fed’s 2% target, but it was a short-term blip, and the Fed didn’t react to it. In less than a year, the PPI was back near 0% and inflation subsided.

Core PCE vs. Headline CPI

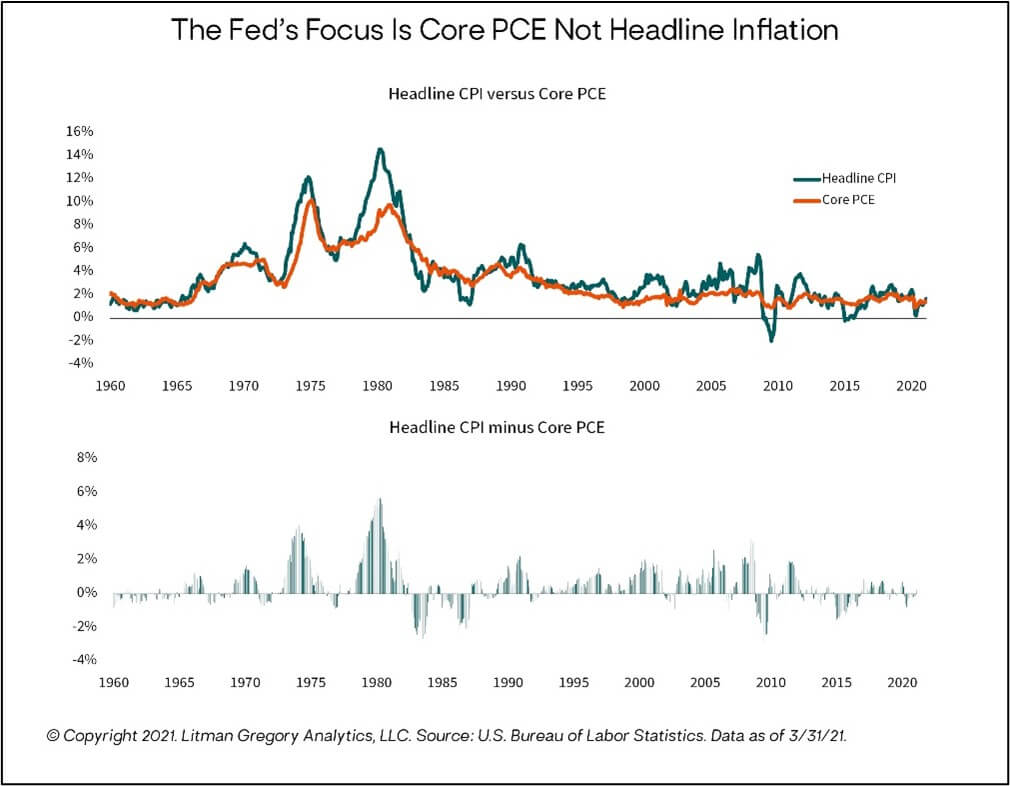

Another important point is that the Fed looks at a different measure of inflation than is normally reported in the financial press—core PCE (personal consumption expenditures). Core PCE strips out not only the volatile prices of food and energy, but a number of other CPI basket items. The Fed’s preferred inflation measure has been one of the lowest inflation measures as you can see in the bottom panel of the chart to the right, which shows the difference between headline CPI and core PCE inflation over time. Notably, core PCE is expected to only modestly exceed the Fed’s 2% target in the next few months. For the Fed to raise rates, it will need to see sustained, material core PCE inflation, not just headline inflation. And we are unlikely to have that even in this reflationary year.

Labor Market Slack & Deflationary Forces

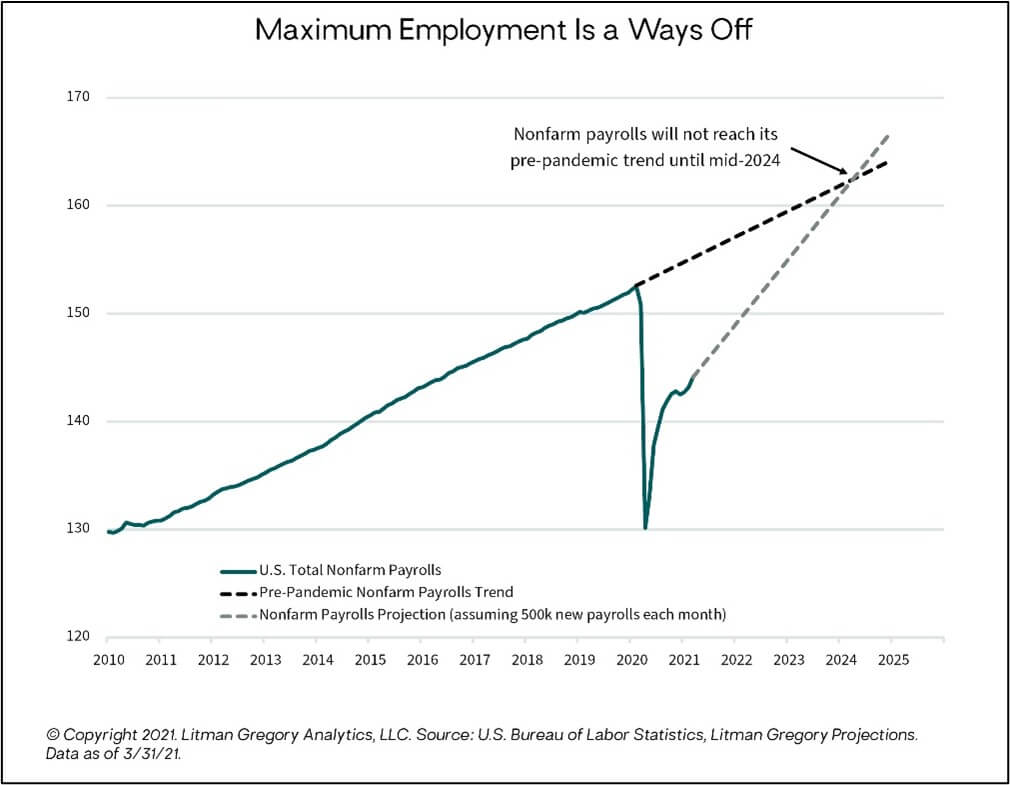

The key fundamental reason why we don’t see sustained inflation as imminent is the tremendous amount of labor market slack. Wage spiral inflation can’t really take hold unless the labor market is near or beyond maximum employment.

The chart to the right shows a rough estimate of how far the economy or employment is away from that point. The black dotted line is the trend growth in non-farm payrolls from February 2020 before the pandemic hit. The lower grey dotted line shows the path of non-farm payroll growth assuming an average of 500K new jobs are added every month. At that rate, it would take until mid-2024 to reach the pre-pandemic employment trend level. If payrolls grew at 700K per month, the lines still wouldn’t cross until the first quarter of 2023. This helps explain why the Fed still doesn’t expect to start raising rates until 2024. Also, even when the unemployment rate was near an all-time low of 3.5% in February 2020, the core PCE was still rising at only a 1.8% rate, below the Fed’s 2% target.

Other mitigating factors: Without continuous large-scale fiscal stimulus from Congress, future years will face a fiscal drag. Not all the previously passed stimulus is being spent right away or at all; some will go to long-term saving or paying down debt. Finally, powerful, structural deflationary forces, such as aging/declining populations and technology adoption, remain with us.

Portfolio Positioning & Opportunities

First of all, many of our current portfolio positions already provide some inflation hedge or are likely to benefit from higher inflation. These include non-U.S. stocks, floating-rate loans, flexible credit-oriented strategies, and trend-following managed futures strategies. With these positions, it is clear we are not betting against inflation. We just don’t believe we need to prepare for a sustained, highly inflationary period over the next few years.

We also don’t tactically react to short-term changes in inflation. The risk of portfolio whipsaw is extremely high because inflation readings can be quite volatile month to month. But if we see the labor market fully recover and then tighten considerably, the economy overheat (grow above its estimated potential), or inflation expectations accelerate higher, we have the ability to increase our portfolio’s inflation sensitivity. A commodity futures fund and possibly natural resource–related stocks are two options. Historically, they have the highest sensitivity to inflation and unexpected inflation. But if this inflation scenario doesn’t play out, these investments’ downside can be meaningful.

On the fixed-income side, we could hedge against higher inflation by further shortening our overall duration, or owning more short-term maturity bonds. This is a lower-volatility way to add inflation protection, but it comes with less return opportunity than commodity-related investments, and much less potential deflation protection. Yields are near zero on short-term bonds except in the riskiest of sectors. So again, and as always, before we decide to make these shifts in our clients’ portfolios, we assess the tradeoffs between the potential risk and reward.

—Litman Gregory Investment Team (May 2021)