Commentary from iMGP CIO—Third Quarter 2021

Market Recap

A September slump put a pause on the global equity bull market. The S&P 500 Index dropped 4.7% for the month, developed international equities (MSCI EAFE Index) fell 2.9%, and emerging-market (EM) stocks (MSCI EM Index) dropped 4.0%. For the third quarter, the S&P 500 was up just 0.6%, MSCI EAFE was down 0.4%, and EM stocks declined 8.1%. For the year to date, the S&P 500 is up an impressive 15.9%, MSCI EAFE is up 8.3%, and the MSCI EM Index is down 1.2%.

The culprit behind EM stocks’ poor recent showing is China. The MSCI China Index was by far the worst-performing stock market in the third quarter, down 18.2%. For the year to date it is down 16.7%. (More on this below.) Chinese stocks comprise roughly 35% of the EM equity index.

Meanwhile, within the broad U.S. market, smaller-company stocks (Russell 2000 Index) dropped 4.4%, and growth stocks beat value stocks for the second straight quarter. The financials sector was the top performer, but the energy, industrials, and materials sectors (all cyclically sensitive) were in the red. These style, sector, and factor performances reflect a somewhat more risk-averse investor mindset, consistent with the COVID-19-related economic growth slowdown during the quarter.

In the bond markets, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield ended the quarter just a bit above where it began, at 1.53%. But it was a roller-coaster ride, with the yield plunging below 1.2% in early August, and then shooting back up in the last two weeks of September. For the quarter, the core bond index return was essentially flat, up 0.1% (Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index). Credit-sensitive bond segments outperformed core bonds, with the high-yield bond index gaining 0.9% and the floating-rate loan index up 1.1% (the ICE BofA ML U.S. High Yield Cash Pay Index and the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index, respectively). For the year to date, core bonds are down 1.6%, while high-yield bonds and floating-rate loans are up 4.6% and 4.4%, respectively.

Looking ahead to the rest of the year, as usual we won’t make any market predictions. We’ll only note that the fourth quarter is historically the strongest seasonal period for stocks. For example, according to Ned Davis Research (NDR), since 1970 the median fourth quarter return for the MSCI World Index is 4.4%, and it has registered a positive return for the quarter more than 75% of the time.

Portfolio Performance & Key Performance Drivers

Our active balanced portfolios saw a drag from our tactical exposure to EM stocks, which significantly underperformed other equity markets as well as core bonds. On the positive side, most of our actively managed/flexible bond funds outperformed core bonds, as did our tactical position in floating-rate loans.

In the rest of this commentary, we’ll walk through three key elements of the U.S. and global macro backdrop: (1) COVID-19, (2) U.S. economic policy, and (3) growth and inflation. We’ll then turn to how these and other factors inform our current outlook for the financial markets. We’ll recap our portfolio positioning and performance expectations. And we’ll conclude with an update of our views on EM equities and China in light of the recent market headlines and regulatory developments there.

The Macro Backdrop

COVID-19

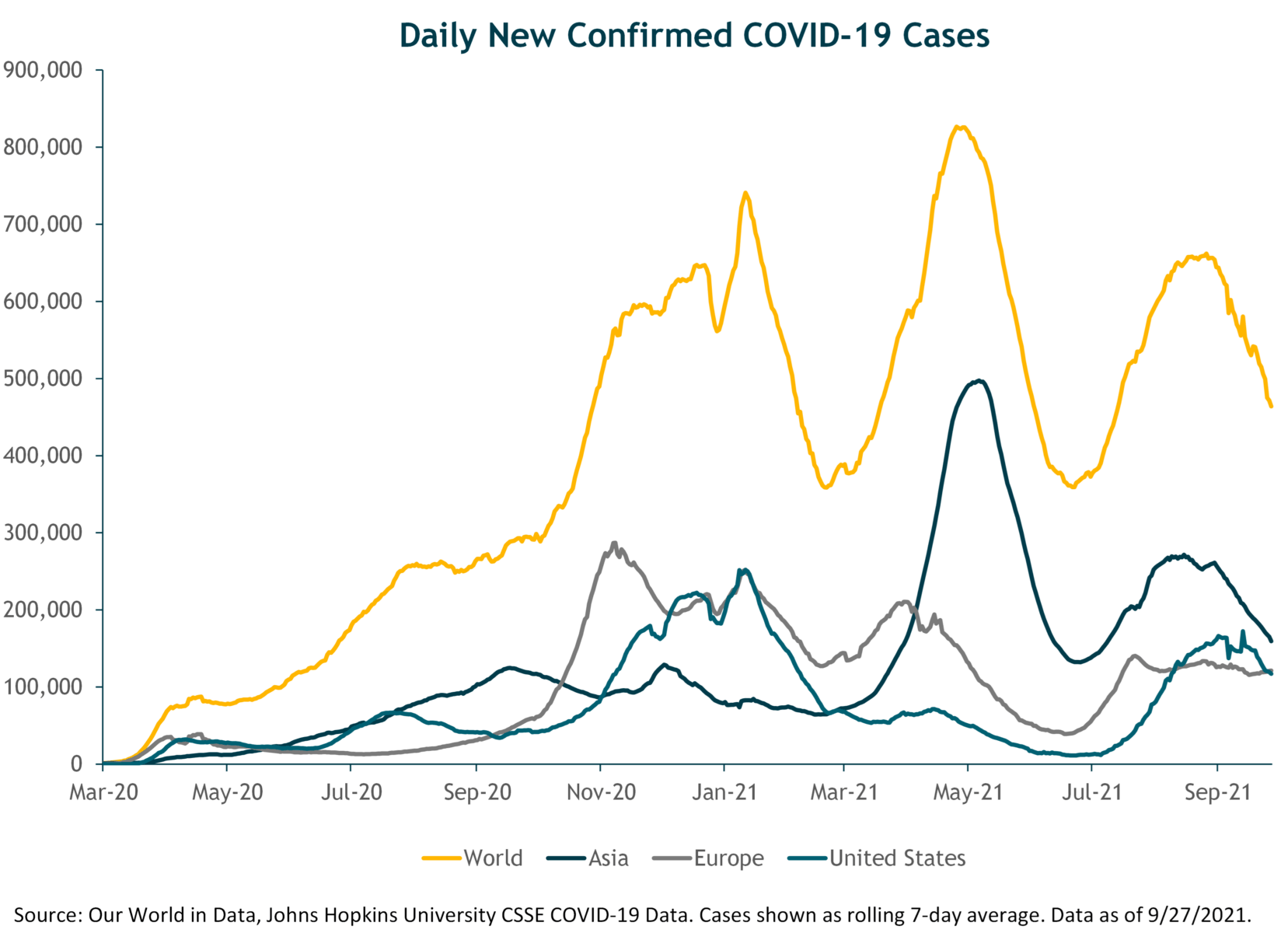

The spread of the highly contagious Delta variant during the summer led to an unfortunate upsurge in daily new cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. However, on the positive side, this fourth wave appears to have peaked globally and is subsiding. Given the ongoing rollout of effective vaccinations—at a rate of ~30 million per day, with more than 6 billion total shots given—and rising immunity, along with social/behavioral adjustments, we believe the most likely scenario is for the virus’s impact on global economic activity to continue to diminish over time.

This conclusion regarding the COVID-19 endgame from a recent McKinsey report makes sense to us, as non-experts in this field:

Our own analysis supports the view of others that the Delta variant has effectively moved overall herd immunity out of reach in most countries for the time being. … A more realistic epidemiological endpoint might arrive not when herd immunity is achieved but when countries are able to control the burden of COVID-19 enough that it can be managed as an endemic disease. [At that point] societies decide—much as they have with respect to influenza and other diseases—that the ongoing burden of disease is low enough that COVID-19 can be managed as a constant threat rather than an exceptional one requiring society-defining interventions.

The path to get there will not be a smooth one—we are not out of the woods by any means. There remains the risk of new, more contagious and/or more deadly variants. We’ll continue to see disparate virus impacts across countries, economies, and industries. But given the overall positive trend in the fight against COVID-19, we do not expect it to derail the global economic recovery in the coming years.

U.S. Economic Policy

There were no major U.S. economic policy surprises during the quarter. On the fiscal policy front, it was mostly business as usual: the usual Washington gridlock, infighting, political posturing, polarization, and dysfunction. It remains to be seen what type of infrastructure spending and tax-hike legislation emerges from Congress in the weeks ahead—not to mention whether there is a Treasury default in mid-October due to the federal debt ceiling standoff. (If so, we expect it will be a short-term disruption.) But as we noted last quarter, no matter what fiscal package is ultimately passed, the economy is now facing a fiscal drag—a negative impact on GDP growth—from the expiration of pandemic spending and support programs, which had boosted growth over the past several quarters.

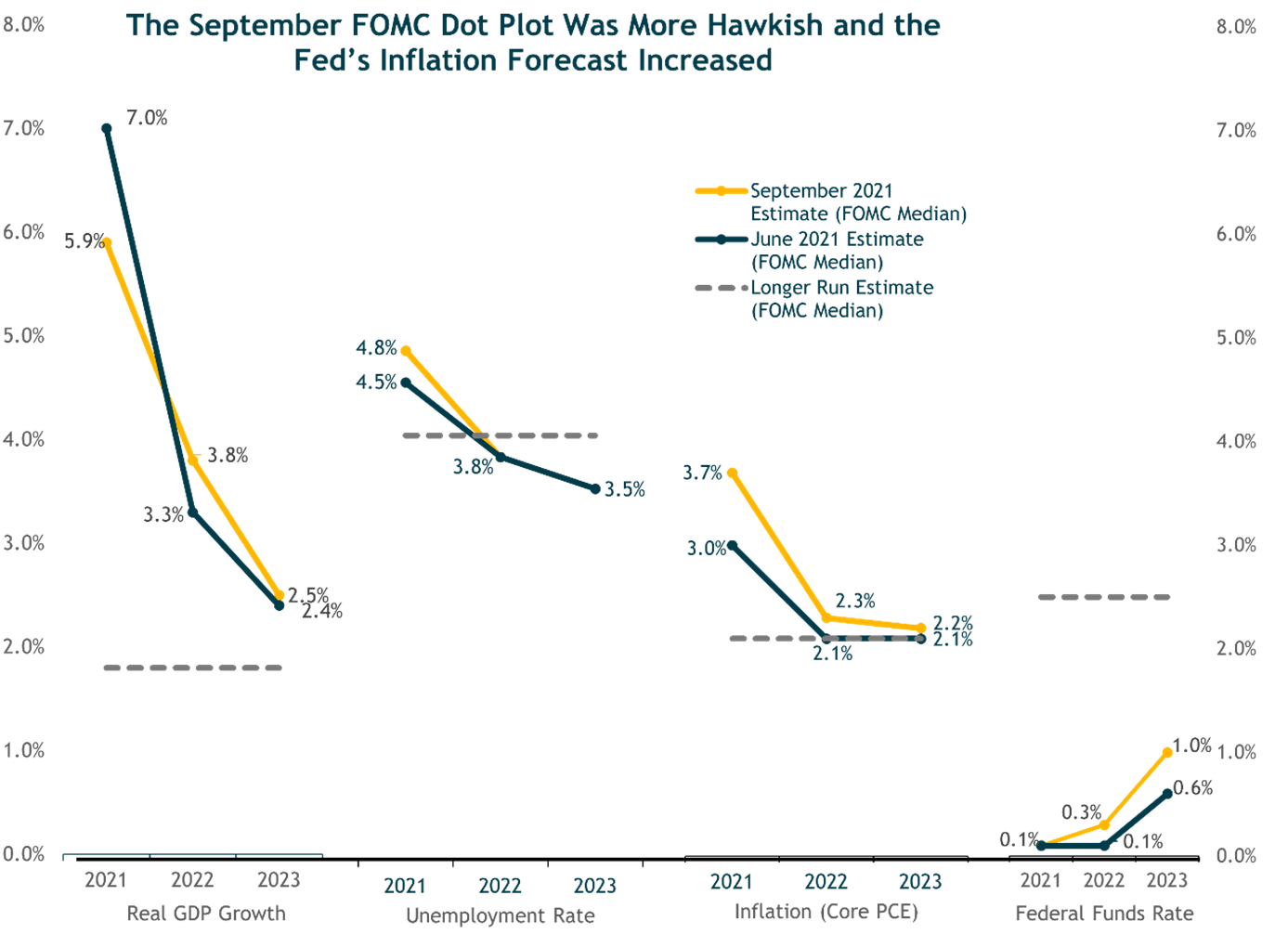

On the monetary policy front, the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced at its September quarterly meeting it is likely to begin tapering its $120 billion monthly quantitative easing (QE) asset purchases starting in November, with an objective of concluding the process and ending QE “around the middle of next year,” according to Fed chair Jerome Powell. This was broadly in line with market consensus expectations.

In addition to the tapering news, the FOMC produced their quarterly economic and interest rate projections. These revealed a modestly hawkish shift compared to last quarter’s meeting. Nine of the 18 FOMC participants now expect to start raising interest rates by the end of 2022, compared to just seven at the June meeting. The median FOMC member also expects an additional three federal funds rate hikes in 2023 and three more in 2024. This would bring the target fed funds rate to 1.75% by the end of 2024. (It reached a post–financial crisis peak of 2.25% in July 2019.) However, it’s important to remember that the FOMC rate projections—the “dot plots”—have never been an accurate forecast of the Fed’s actual interest rate moves several years out. As we’ve often said, no one, not even the Fed itself, knows what the Fed will actually do two or three years from now.

Having said that, and without needing to precisely predict interest rates, we think the odds are high that short-term rates will rise but still remain low by historical standards and also below the rate of inflation for several more years. That is to say, monetary policy will likely remain accommodative and broadly supportive of financial asset valuations, but increasingly less so over time.

Economic Conditions: Growth and Inflation

The FOMC’s updated forecasts for growth and inflation reflect the evolving economic consensus. The Fed sharply lowered its median GDP growth forecast for 2021 to 5.9%, from 7.0% in June, a function of the Delta-driven growth slowdown during the summer and ongoing production shortages and supply-chain bottlenecks (e.g., semiconductor and shipping container shortages).

But although global and U.S. economic growth rates slowed in the third quarter, they are still solidly above trend, and the near-term (6– to 12-month) risk of recession remains low, absent the always-present possibility of an exogenous shock (e.g., geopolitical conflict, massive cyber-attack, global pandemic, etc.).

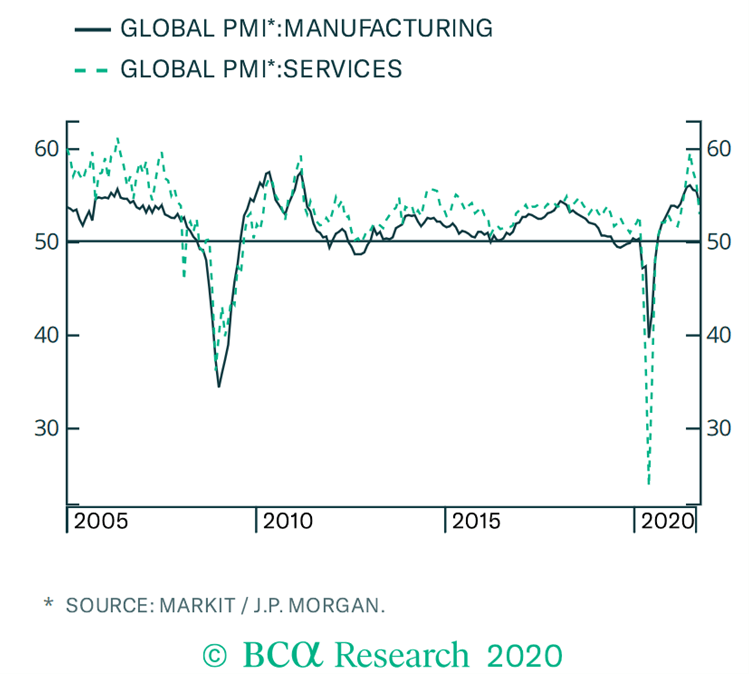

The accompanying global Purchasing Manager Index (PMI) charts show the deceleration in global growth since May—particularly for the Services sector, which was harder hit by the delta variant this summer. Importantly, however, the PMIs remain in “expansion” territory, with readings above 50.

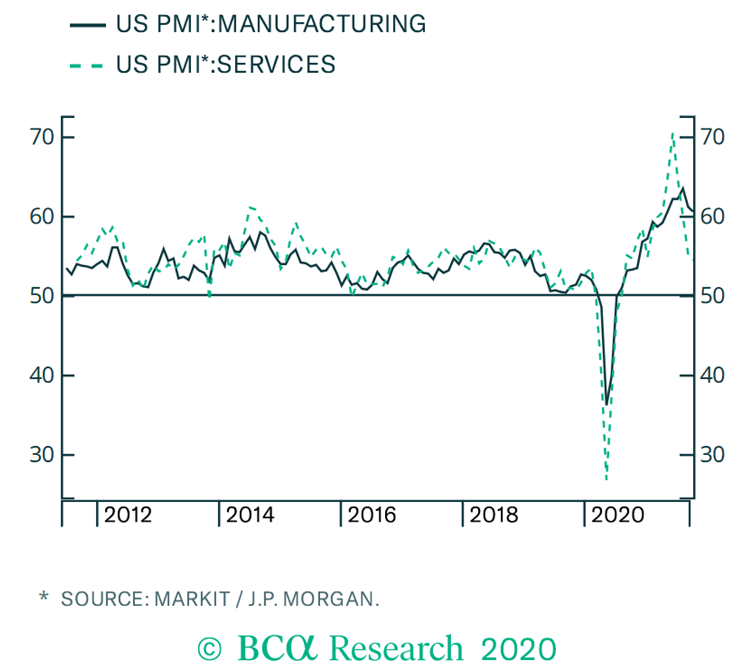

Business activity in the United States also slowed sharply over the summer, with the U.S. Composite PMI sliding to 54.5, its lowest level in a year. As was the case globally, U.S. services and manufacturing activity continued to grow, but at a slower rate. As we’ll discuss later, this type of growth deceleration typically implies weaker stock market performance.

Meanwhile, along with reducing its 2021 growth forecast the FOMC sharply increased its median core inflation forecast for this year to 3.7%, up from 3.0% in June, pointing to ongoing supply-side disruptions (e.g., new car prices continue to rise). The Fed also slightly boosted its projections for core inflation in 2022 and 2023.

We provided an in-depth update of our view on inflation in our Second Quarter 2021 Commentary and won’t rehash all those points here. Since June, the inflation data have continued to give mixed messages. The “transitory vs. sustained high inflation” debate remains unresolved. We are still in the “mostly transitory but higher than 2% inflation” camp.

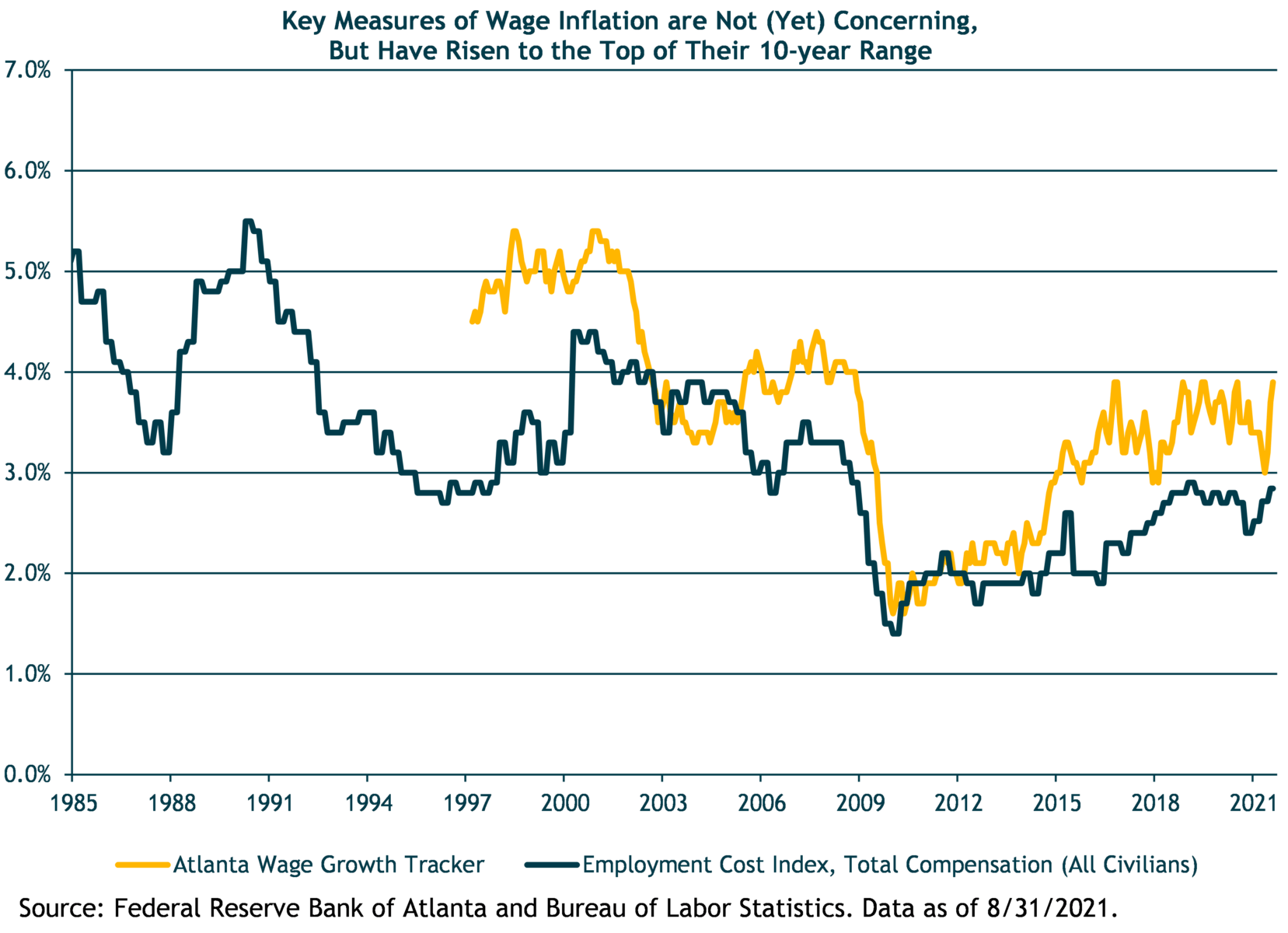

Our base-case view is that the U.S. economy appears to still have significant slack and excess capacity (e.g., employment is still 5 million jobs below the pre-pandemic level), minimizing the risk of significant, sustained, and broad-based inflation. We don’t yet see the breeding ground for the type of self-reinforcing wage-price spiral necessary to generate sustained high inflation rates. But again, there are crosscurrents in the recent data and our view will continue to evolve with the data.

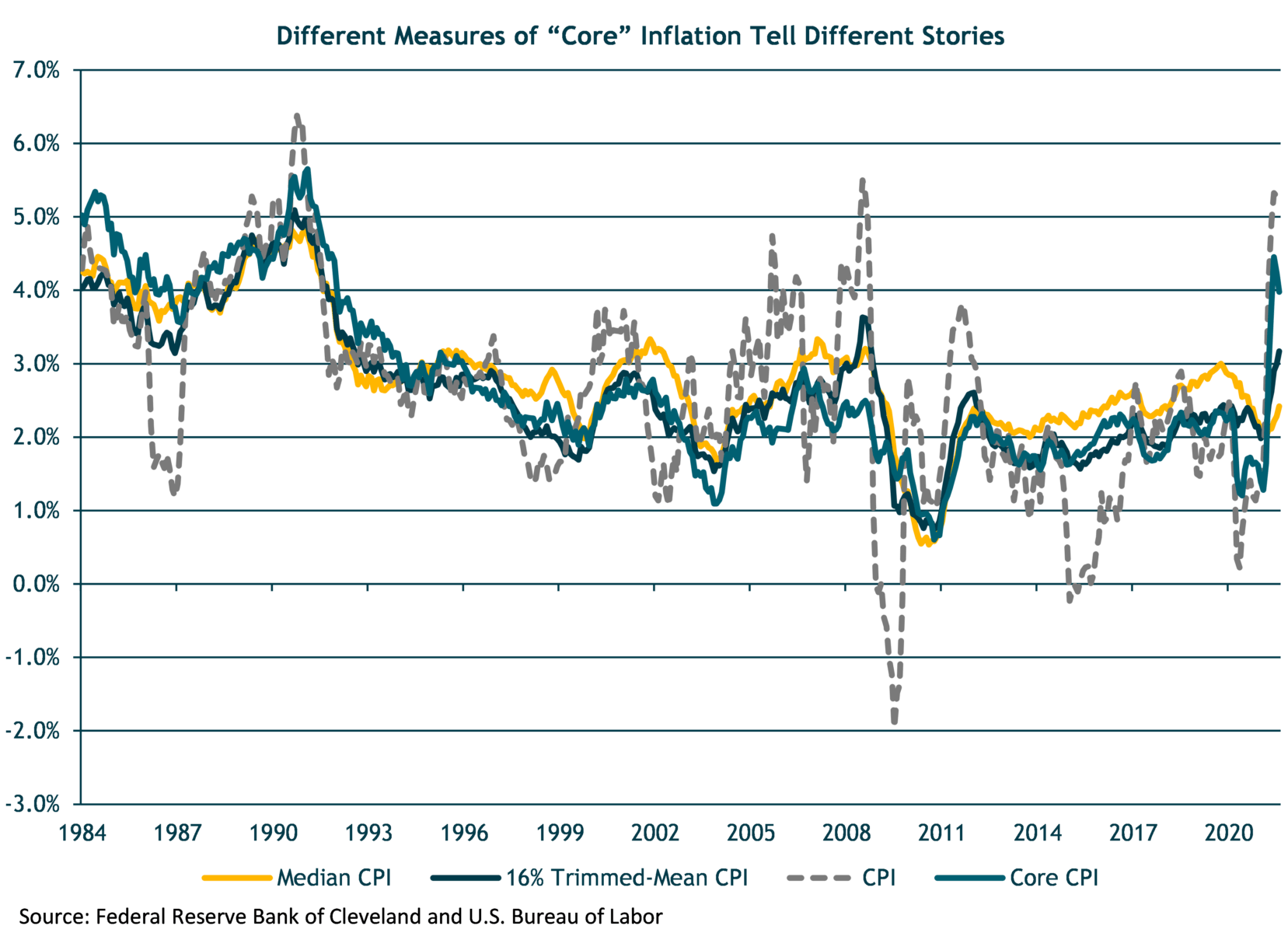

For example, while key measures of wage inflation remain within a normal historical range, they have increased over the past few months. The same is true for some key measures of inflation expectations, and also for the Fed’s median and trimmed-mean measures of core inflation. Shelter prices (measured by the government as rent and “owner’s equivalent rent”) account for roughly 40% of core CPI and are now on the upswing following the sharp, sustained rise in national home prices, which have surged a record 19% in the past twelve months.

On the other hand, August’s CPI inflation numbers came in below consensus expectations. (Month-over month core CPI rose just 0.1%.) And the majority of recent inflation increases still look to be driven primarily by pandemic-related supply and demand shocks that should continue to normalize over the next year, assuming the pandemic comes further under control. We also give some credence to Powell’s (and other Fed governors’) statements that the Fed will act to tighten policy if core inflation stays elevated and/or medium- to longer-term inflation expectations become unanchored. But that remains to be seen.

Financial Market Outlook

Moving from the macro to the markets, over the next 12–24 months or so we see the strongest likelihood for continued positive returns for equity and credit markets (and “risk assets” in general), driven by continued economic and corporate earnings growth—albeit decelerating in the United States—and supported by still-accommodative monetary and fiscal policy—albeit less so in the United States.

This macro backdrop also suggests 10-year Treasury yields are likely to rise—although we don’t expect a sharp increase, which means a poor environment for core bond returns, both in absolute terms and relative to other asset classes and alternative strategies.

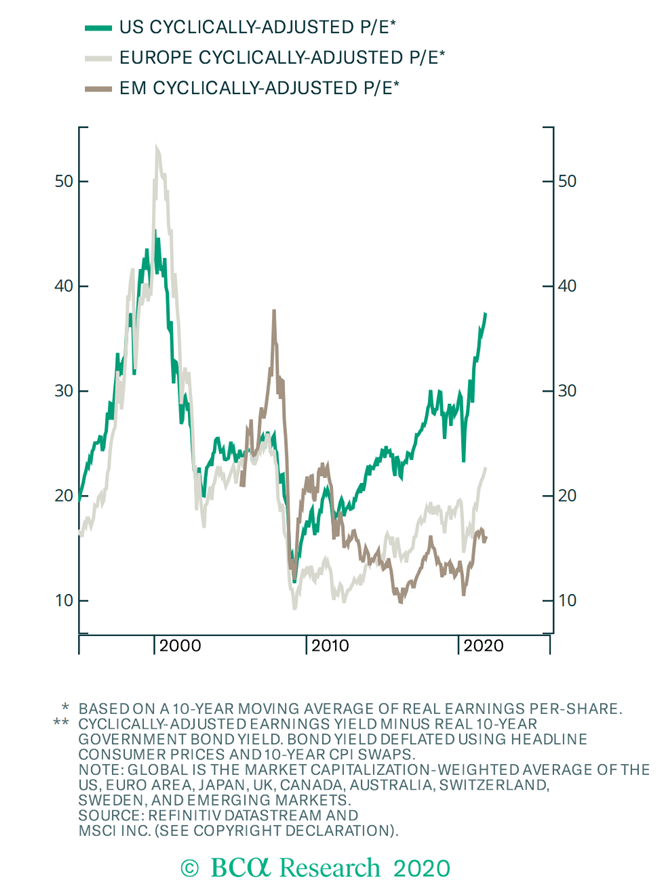

Further, we expect international and EM stock markets to outperform the S&P 500, due to their higher beta (or sensitivity) to global growth, their larger potential for earnings acceleration (and positive earnings surprises) from still sub-par levels that have lagged the U.S. recovery, and their much lower starting equity market valuations. Therefore, we see potential for strong returns from both a cyclical earnings rebound and increased valuations (price-to-earnings multiples) in foreign stock markets over the coming years.

For the U.S. market, with valuations already near all-time highs, we see little room for valuation expansion. Earnings growth should therefore be the primary driver of U.S. equity returns. But as we discuss next, the U.S. market is also facing some near-term risks that could lead to a market correction (a roughly 10% market decline), but unlikely a bear market (20%+ decline).

Reasons for Near-Term Caution on U.S. Stocks

(1) A growth scare

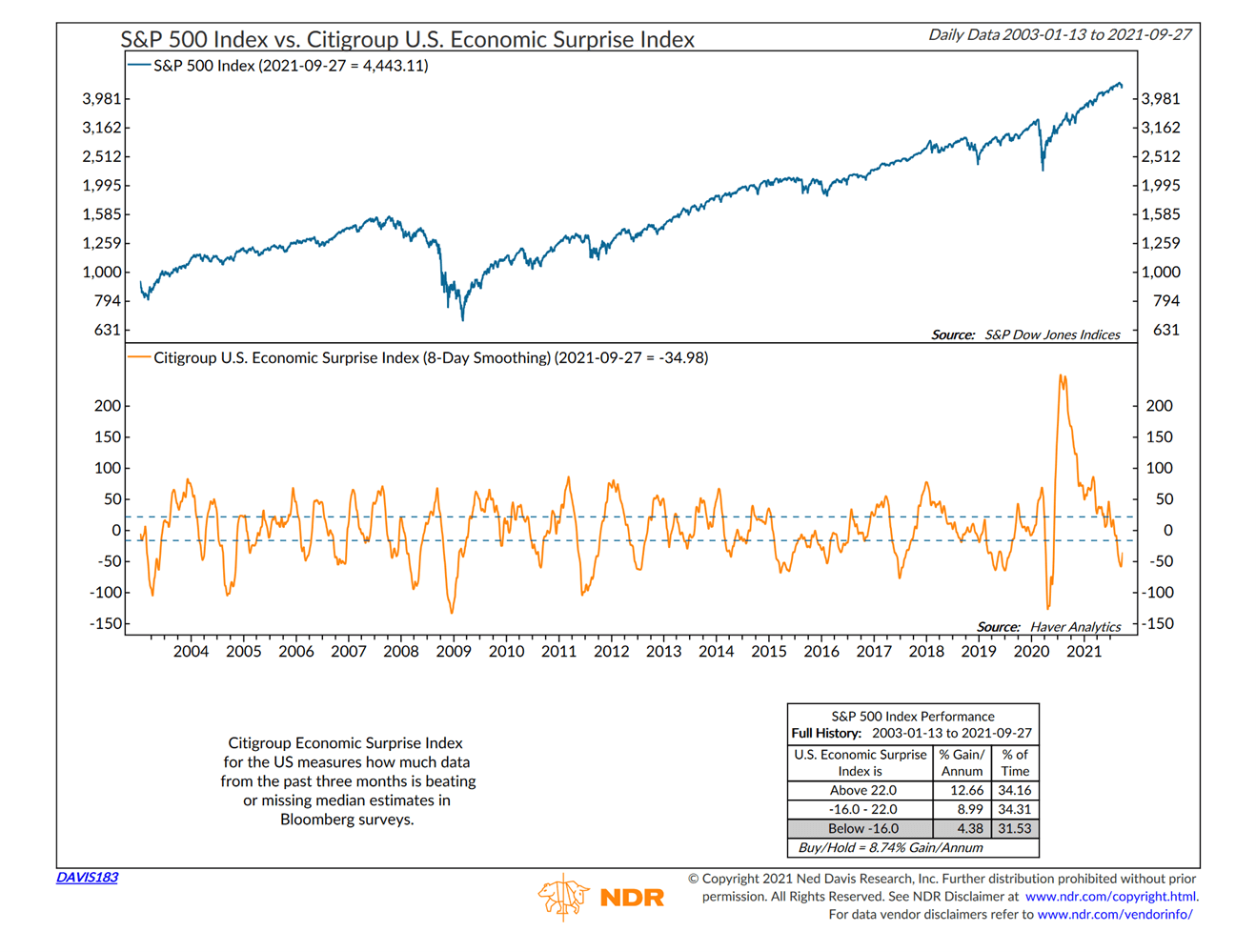

We noted above that economic growth momentum in the United States and abroad decelerated in the third quarter. While some slowdown was to be expected coming off the extremely strong second quarter, the recent economic news has been generally worse than the consensus expected, as can be seen in the Citi Economic Surprise Indexes. And as the following chart from NDR shows, negative economic surprises are typically negative for stock market returns.

So far this year, the U.S. markets have remained resilient in the face of these disappointments. However, there comes a point where equity and other risk asset markets can no longer shrug off bad fundamental news. And this risk is heightened when growth expectations—and the valuations that reflect those expectations—are high. Put differently, the higher the expectations/valuations, the bigger the downside risk if those expectations are not met.

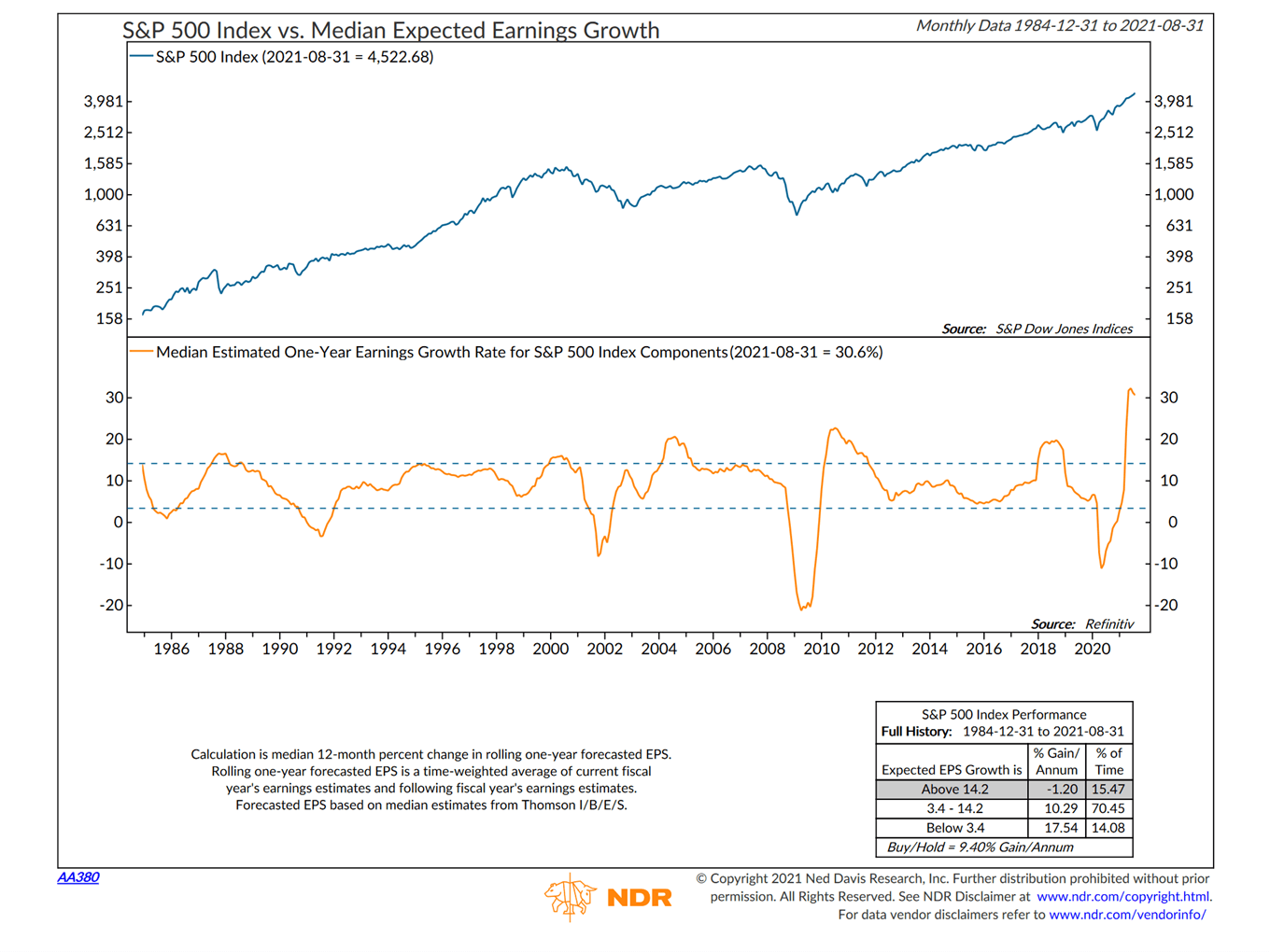

Throughout 2021, S&P 500 earnings repeatedly and spectacularly beat consensus expectations, driving the U.S. market index to one new high after another. But as is the nature of human behavior and financial market cycles, excessive (earnings) optimism ultimately sets the stage for (stock market) disappointment, as the accompanying NDR chart shows.

So this is a key shorter-term U.S. market risk—one that we would put under the general heading of a “growth scare.” A “mid-cycle” market correction is fairly common during this phase of the economic and earnings cycles. There are any number of potential catalysts right now, although some are lower probability in our view than others. Some examples:

- There is a COVID-19 resurgence during the winter months that leads to reduced economic activity and investor pessimism/risk aversion.

- The fiscal growth drag from the expiration of pandemic support programs is more severe than expected.

- Washington political gridlock prevents passage of additional infrastructure spending that the market is already expecting.

- Corporate tax rate hikes are larger than expected and/or have a bigger impact on earnings than currently expected. On this point, we have seen estimates ranging from a four to seven percentage point hit to S&P 500 earnings growth in 2022 from higher corporate tax rates. But the market does not appear to have fully discounted this yet.

- A federal debt ceiling/Treasury default debacle causing a short-term but severe disruption.

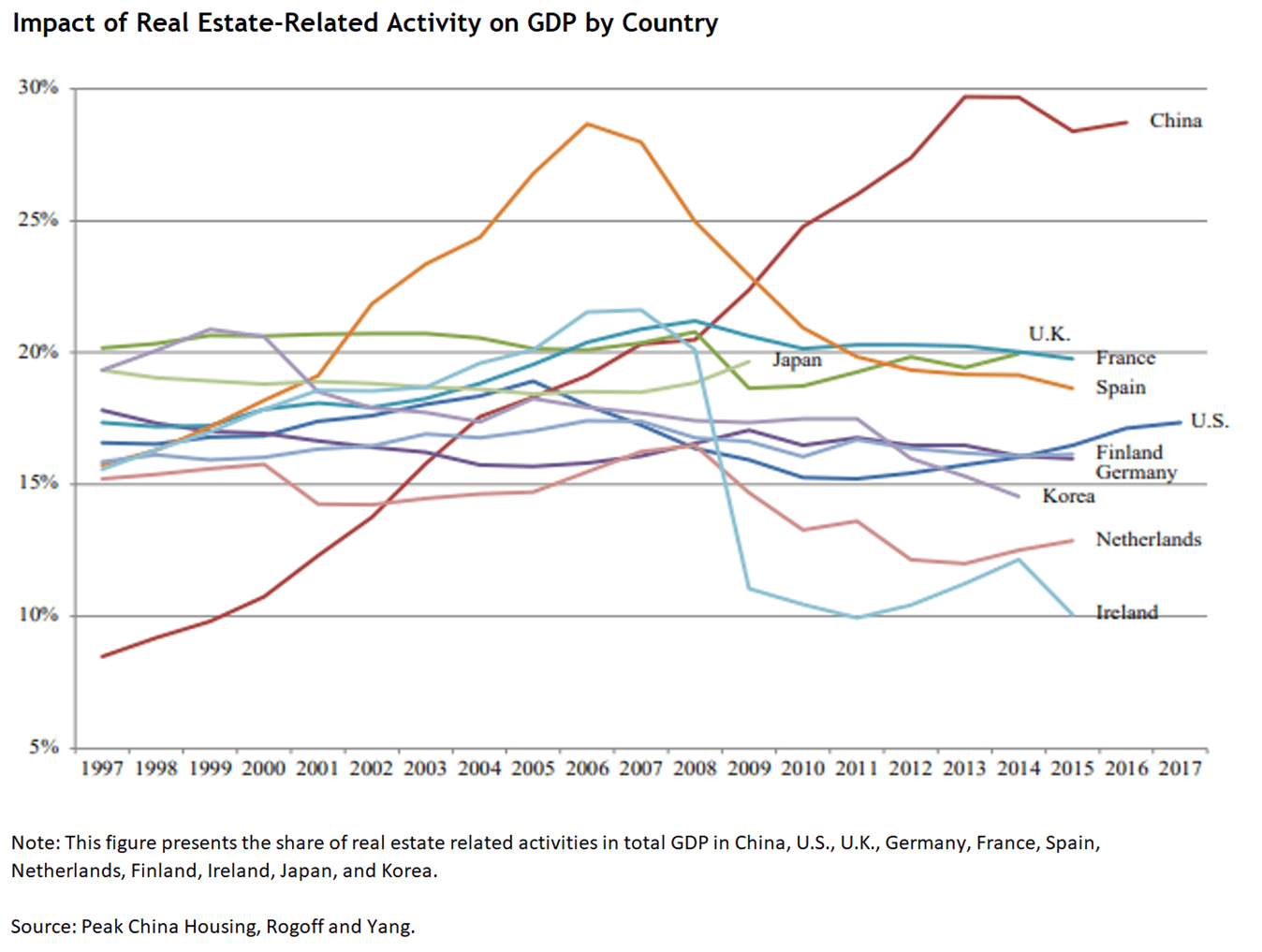

- Systemic contagion from a China Evergrande debt default. (We view this as low probability as we discuss later in this report.) Even absent an Evergrande contagion crisis, there could be a hit to China’s economic growth—and therefore global growth—due to China’s clampdown on its property/housing sector, which comprises a large share (~30%) of China GDP.

(2) An inflation scare

A second type of market risk stems not from a negative growth shock, but from an inflation shock. If incoming inflation data (e.g., wages, core inflation metrics, inflation expectations) strongly support the “non-transitory high inflation” argument, the market and Fed are likely to respond by pushing interest rates meaningfully higher. This would likely hurt investor sentiment and hit valuation multiples, particularly for the long-duration high-growth stocks that have been the primary beneficiary of the recent period of exceptionally low yields and low inflation, (e.g., the FAANG stocks, short for Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google/Alphabet). Cyclical and value stocks could perform relatively well in this environment, but the tech-heavy S&P 500 would likely not.

It is also possible the Fed’s policy tightening response to an inflation scare would be so severe as to push the economy into recession. (Fed tightening cycles have historically been the primary catalyst for recessions. And most bear markets are associated with recessions.) This is the argument many Fed critics have been making: By already waiting too long to start tightening monetary policy, the Fed is brewing inflationary pressures and financial imbalances that will ultimately require an extremely aggressive tightening response, pushing the economy into a deeper recession than otherwise would have been the case.

But barring a recession, and given our base case that this global economic cycle still has legs, we would expect tighter-than-expected Fed policy to cause at worst a stock market correction—setting the stage for a further market rally rather than a full-on bear market.

Portfolio Positioning

We made no changes to our portfolio allocations in the third quarter. They remain well-diversified and balanced across a range of global asset classes, risk factor exposures, and investment strategies, each of which has different expected performance depending on the macro and market environment that unfolds.

We believe the portfolios are well positioned to generate relatively strong returns in our most likely baseline scenario of a continued global economic recovery with moderately rising interest rates and inflation and decelerating growth in the United States. But our balanced portfolios should also prove resilient in the event of a “left-tail” scenario (a negative scenario among potential outcomes), such as a growth or inflation scare as discussed above.

Overall, most of our portfolios are positioned with (1) a small overweight to global equities, driven by our tactical overweight to EM stocks, (2) a large underweight to core bonds in favor of flexible, shorter-duration, credit-oriented bond and floating-rate loan funds, and (3) positions in lower-risk and diversifying alternative strategies. Our private client portfolios also have allocations to selective private equity and private real estate investments, where appropriate, that we believe have strong medium-term return prospects and also provide beneficial portfolio diversification.

Over our five-year tactical horizon, we estimate base-case returns in the mid to upper single digits, with lower returns for U.S. stocks and core bonds and higher returns for our EM and private equity investments for our balanced portfolios.

Within our public equities allocation, we have balanced exposure across the value-blend-growth style spectrum. We do see potential for value and cyclical stocks to strongly rebound (again) as COVID-19 recedes and inflation and interest rates rise. And after an unusually long and severe period of underperformance versus growth stocks, value stocks, in aggregate, look particularly cheap versus growth. But we also want to maintain long-term, strategic exposure to high-quality, innovative growth companies with strong competitive advantages selling at reasonable valuations.

An Update on Our Outlook for Emerging Markets & China

With China’s economy and financial markets in the headlines recently (e.g., the large property developer Evergrande’s looming default), and EM stocks’ strong performance earlier in the year having reversed, we wanted to provide a more in-depth update of our views on this important asset class.

Strategic Perspective

Before diving into recent events and our tactical (five- to 10-year) outlook, it is important to remember how we think about our strategic portfolio asset allocations. The strategic allocations are based on a long-term view—10 to 20 years—of what the right mix of assets in our opinion should be, for a given client/portfolio risk level.

We believe emerging markets broadly, and China specifically, offer unique risks and opportunities and will be an important diversifier and return-generator for client portfolios over the long term. As such, we want to have a strategic allocation to it that is large enough to have a meaningful portfolio impact. Barring a compelling tactical view, we stick to our strategic portfolio allocations (across all asset classes) and periodically rebalance to those target allocations. This lends valuable discipline to our investment process. It also is a measure of humility in that it acknowledges that markets are generally efficient in pricing in most risk factors over time and that the future is uncertain and unpredictable.

Moreover, the evidence is overwhelming that most investors detract from their long-term investment returns by overtrading their portfolio in response to short-term market gyrations or news flow. (Related, they also hurt their returns by chasing performance, whether the recent “hot” fund manager or asset class). So, the key reasons why we have a strategic allocation to EM equities (and therefore China equities, which represent roughly 35% of the EM equity index) is diversification and gaining long-term access to a huge and important part of the global economy and investment opportunity set.

Looking at Chinese stocks specifically, our strategic allocation currently implies a roughly 4%–5% weighting in a typical balanced portfolio. (If you factor in our current EM tactical allocation, the China equity weighting is roughly 5%–6%.) We think this is very reasonable considering the risks and opportunities we see. Correspondingly, our balanced portfolio strategic allocation to U.S. stocks, which we consider a high-quality growth asset, is 36%—eight or nine times larger than our strategic China equity exposure. Given the relative risks and opportunities we see in both markets over the very long term, we think this strong tilt in favor of U.S. stocks is more than sufficient, while still enabling valuable portfolio diversification and return-generating opportunities outside the United States.

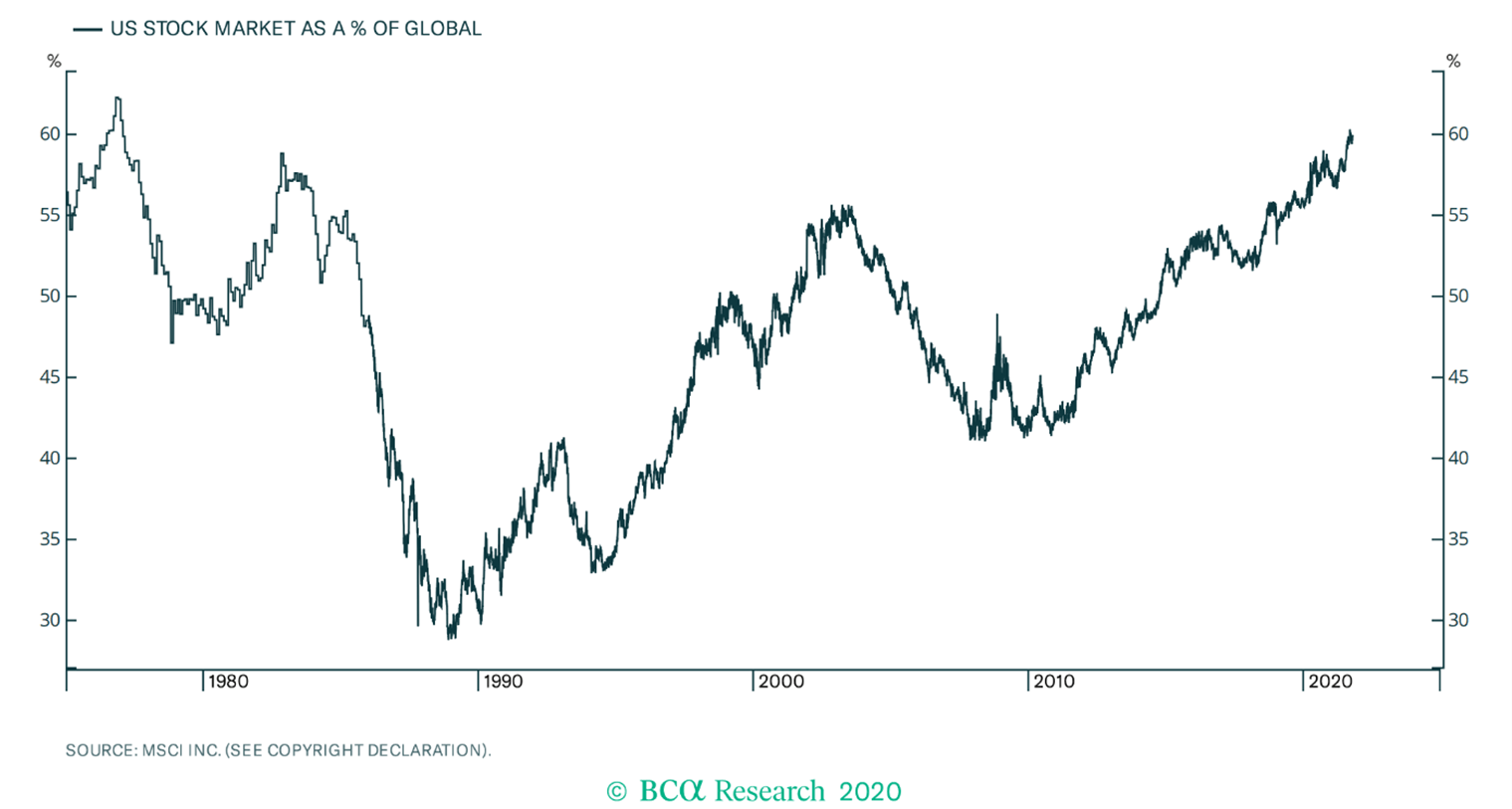

As a percentage of our total global equity exposure, our strategic allocation to U.S. stocks is 60%. EM stocks and developed international stocks are 20% each, strategically. As the following chart shows, the extremely strong performance of U.S. stocks over the past 10-plus years has now pushed its share of the total global stock market up to 60% (near its all-time high) from the low 40% range 10 years ago. In other words, our 60% strategic U.S. allocation is now in line with its global market-cap weighting. So, viewed from this global market perspective as well, we are quite comfortable with our current strategic allocations to U.S. and non-U.S. stocks.

Finally, it is worth a reminder that relative to the overall global equity market index weightings (as represented by the MSCI ACWI Index), we have in effect funded our roughly 5% strategic overweight to EM stocks from developed international stocks, not U.S. stocks. Our 20% strategic allocation to developed international stocks is 5% lower than their roughly 25% weighting in the ACWI index. Again, as we look forward at the growth, fundamentals, and investment opportunities within emerging markets versus Europe and Japan, we think this makes sense.

Tactical Perspective

Moving on to our current tactical positioning, we remain overweight to EM stocks in most of our portfolios. In our more risk-tolerant balanced portfolios, we are funding this tactical overweight primarily from core bonds. So we are essentially using EM stocks to be overweight equities overall versus bonds, a risk we are comfortable taking given where we are in the economic and market cycle. In our more conservative portfolios, we are not taking as much equity risk and are funding the EM overweight from U.S. stocks.

Despite specific EM risks, which we will discuss next, and factoring in their lower expected earnings growth rate and lower quality versus the S&P 500, we believe EM stocks are quite cheap, as the accompanying chart demonstrates.

In our view, it is likely that as the world emerges (again) from the COVID-19 pandemic we will see a reflationary growth cycle re-emerge that will be positive for both EM earnings and valuation multiples.

We’d note that we have decided not to raise our EM earnings estimates as we were considering prior to China’s recent severe crackdowns against after-school tutoring companies. As a result, we are factoring in some moderation in our medium-term EM earnings expectations due to recent regulatory changes, including property-related deleveraging, that are geared toward achieving China’s social goals (and clearly Chinese president Xi Jinping’s personal political goals as well).

Key Risk & Question

The biggest question mark or uncertainty for us right now relates to the Evergrande situation, which in our view highlights an incongruity: China’s goal to reduce income inequality and, at the same time, to also reduce the leverage and size of the property/housing sector of its economy. Unlike the for-profit education sector, the property/housing sector is a bigger problem in terms of both worsening inequality and how large it is as a share of China’s economy, accounting for roughly 30% of GDP and roughly 60% of household assets (estimates vary). (As a comparison, only about 25% of U.S. household assets are in property.) It raises the question: Can China achieve both goals at the same time?

While the answer remains uncertain, at this point the weight of the evidence we have been able to collect suggests it can. See our recent piece, Research Update: Evergrande and China’s Property Sector.

First, the Evergrande debt problem specifically, and the entire property sector deleveraging, seems manageable. The majority of Chinese property developers meet the “three red lines” criteria China has laid out to mitigate systemic risks stemming from excessive property investment and speculation.

But it is increasingly clear Evergrande and a few others do not meet those red lines and are likely to default. China is trying to inflict losses on Evergrande’s private investors, and in turn reduce moral hazard (where investors assume the government will always bail them out in a crisis), without causing widespread financial contagion. Critically, the Chinese government stands ready to step in to manage and minimize widespread damage from the Evergrande default (an “orderly” default) given it is the majority owner of, and effectively controls, the financial system.

Second, it is unrealistic to believe that this problem or incongruity will be solved overnight. Very likely, China will de-lever the real estate sector slowly, in favor of other sectors it wants to grow and is championing. This is also creating investment opportunities that our active EM and international managers are looking to exploit.

Third, China’s government will be highly motivated to prevent a crisis stemming from a potentially disorderly decline in property prices, given the huge amount of household savings that reside in the property sector.

Of course, the risk is that China is not able to manage this balance well and there is a major financial crisis, a risk we have worried about in the past and do not ignore today despite our relatively optimistic view. Outside of a financial crisis, there is the medium- to longer-term risk that by clamping down on the huge property/housing sector, China’s overall economic growth is sharply curtailed beyond what the market is already expecting.

Summing Up

To conclude, we believe on balance the recent regulatory and property sector–related actions, if executed well, will lower systemic risk and likely result in a more sustainable growth path for China. On the regulatory side, thus far our discussions with managers suggest while there may be a hit to the long-term earnings power of some consumer-facing e-commerce companies, it will likely not be material. Meanwhile, their stock prices have already taken a big hit.

Most companies will comply with the new requirements and restrictions and move forward as it is good business, as long as the drive to meet social objectives is not taken so far as to damage long-term company profitability. We will continue to monitor this through our in-depth manager conversations and other sources, but widespread damage to private enterprise would not seem to be in China’s own long-term growth interests.

Importantly, there are many sectors the Chinese government is supporting and that may offer investment opportunities (although this doesn’t guarantee these industries will be profitable). As noted above, before the recent regulatory actions gained steam in China, we were considering raising our EM earnings forecasts. In deciding not to do so we believe we have adequately factored the hit to long-term EM earnings power related to these policies. Separately, the pandemic has dragged on and that has delayed the recovery in earnings we expect to see, but it has not eliminated it, in our view.

In sum, at present we are staying the course while looking for more clarity on the regulatory front. We are comfortable with our tactical EM overweighting, though we are mindful of the risks from the ongoing deleveraging in the China property sector. We are actively analyzing these risks. If the evidence and our analysis suggest we should change our tactical positioning or strategic outlook, we will do so.

Closing Thoughts

Most of this commentary has focused on our investment outlook over the short to medium term—the next few years. Our base case over this period remains relatively sanguine, as we expect the economic and earnings growth cycle, interest rates, and government policy to remain broadly supportive of equities and other risk-asset markets.

However, our five-year medium-term tactical analysis suggests we should be prepared for an extended period of lower absolute investment returns—certainly, in our base case, much lower for U.S. stock and core bond market indexes than the last five to 10 years. (The S&P 500 has gained 17% annualized over the past 10 years and core bonds are up 3% annualized.)

Absent significant further U.S. equity valuation expansion (higher price-to-earnings multiples), from already near-record-high levels, double-digit U.S. market annualized returns are extremely unlikely. What has driven larger-cap U.S. stock valuations to these record highs has been the decline in bond yields to all-time lows combined with above-trend earnings growth (largely due to the mega-cap tech/Internet leaders). Mathematically and economically, that is extremely unlikely, if not impossible, to repeat over the next five to 10 years, given where we are now starting from in terms of yields, profit margins, and earnings growth.

Nevertheless, in our medium-term “upside” scenario we estimate still-attractive upper-single-digit returns for U.S. stocks. And in our base case, while their absolute returns are uninspiring, we expect U.S. stocks to earn an adequate excess return premium above core bonds. So, we are only modestly underweight to U.S. stocks in our balanced portfolios.

Meanwhile, expected returns for non-U.S. equities—EM equities in particular—remain absolutely and relatively attractive over our tactical time horizon, which is the primary reason for our tactical overweight to them. But as we wrote at the end of our second quarter commentary—and as we experienced with EM stocks in the third quarter—equity investors should be prepared for a bumpy ride.

—Jeremy DeGroot, CFA, iMGP Chief Investment Officer (10/8/21)