Understanding Bond Math During Downturns

Many investors have not experienced significant losses in the bond portion of their portfolios in their investment lifetimes. While seeing declines in what was intended to be the “safe” portion of your portfolio can be jarring, it is helpful to understand bond market math and consider the psychology versus reality of bond price declines.

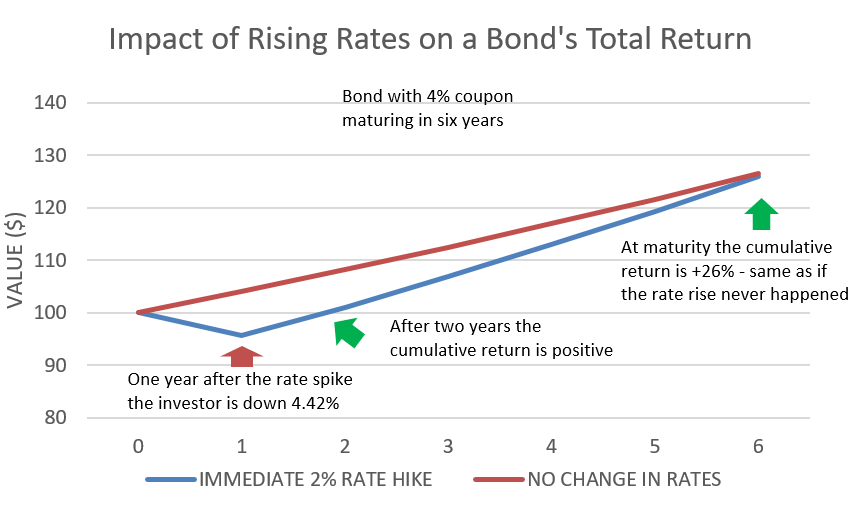

A key point is that unless the corporation or government that issued the bond defaults, a bond with a par value of $100 and an interest rate of 3% will definitely return $100 at maturity, and definitely earn 3% interest along the way, even if the value of the bond price temporarily declines because rates went up. (Yes, credit/default risk matters but it’s a separate part of the equation and not really the driver of concern for everyday investors when rising rates push bond prices down.)

What should you make of that? One way to think about why existing bond prices go down when prevailing rates go up is that the “missing” interest of the previously issued lower-coupon 3% bond versus a new issue yielding 4% is “front-loaded” into the price of the 3% bond (meaning the price of the 3% bond drops to make up for the “missing” interest). An investor holding the 3% bond to maturity won’t actually experience a loss, they will just get less yield along the way and that lower yield is what reduces the current value of the bond.

In the case of bond mutual funds, where lots of bonds are bought and sold along the way, the same thing effectively happens even if there are a lot more moving parts as individual issues are bought and sold within the portfolio. In effect, higher bond yields provide opportunities to invest in higher-yielding bonds, setting a fund up from higher future returns.

So when rates rise and bond prices fall, the long-term return isn’t as good as it would have been, but it’s probably not as bad in the shorter term as you think it is when reading a statement.